Wetlands are among the most important ecosystems in North America, supporting birds as breeding grounds, migration stopovers, and winter refuges. For birders (or birdwatchers), they offer some of the best opportunities to see and hear many species of birds in open spaces. Beyond birdlife, wetlands protect people by filtering water, reducing floods, and sustaining fisheries. This overview provides the broader context for wetlands across the continent and is designed to supplement my state-specific guides to wetland birds.

What exactly are wetlands?

Wetlands are ecosystems where land and water meet, remaining saturated either permanently or seasonally. These habitats support unique plant and animal communities adapted to waterlogged soils and fluctuating water levels.

Wetlands are difficult to define

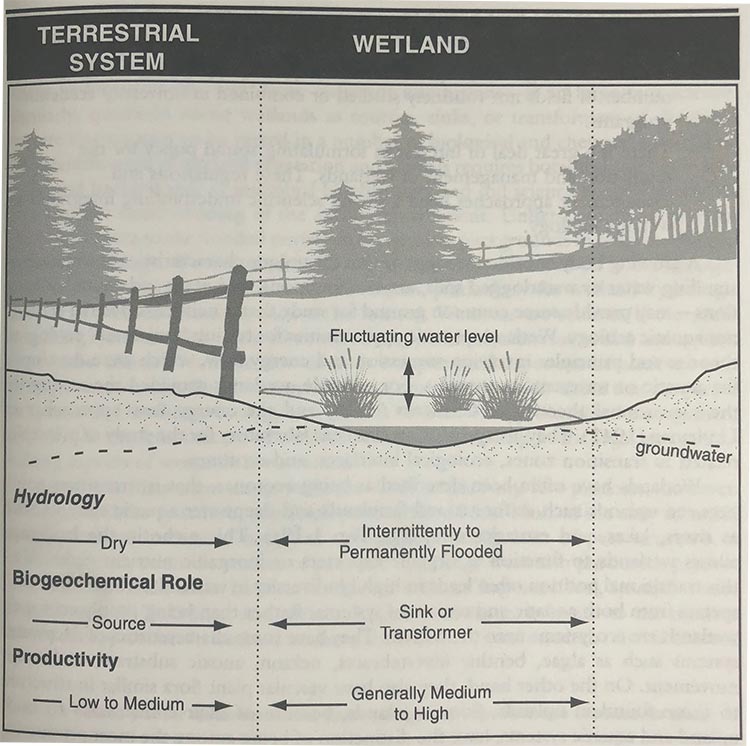

Defining wetlands is challenging because they exist on a continuum between terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Their boundaries shift with rainfall, tides, and seasonal flooding, making them dynamic and variable over time. In addition, no single characteristic—water, soil, or vegetation—always applies in every case. This variability means that scientific, legal, and management definitions often differ.

Broadly speaking, wetlands are often located as ecotones (transitions) between dry terrestrial systems and permanently flooded deepwater aquatic systems such as rivers, lakes, estuaries, or oceans.

Wetlands can also be found in the landscape as isolated basin with little outflow and no adjacent deep-water systems.

One of the most important ecosystems on Earth

Wetlands are considered one of the most important ecosystems on Earth because they provide a unique combination of ecological, climatic, and economic benefits unmatched by most other habitats.

Wetlands act as natural water filters, trapping pollutants and improving water quality. Their ability to store floodwaters and buffer coastlines makes them essential for protecting human communities from storms and flooding.

Wetlands also serve as massive carbon sinks, storing billions of tons of carbon in soils and vegetation, which helps slow climate change.

Importance of wetland for birds and birders

Biodiversity is another key reason: wetlands are among the most productive ecosystems, supporting thousands of species of plants, fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and especially birds. In North America, more than 50% of bird species rely on wetlands at some stage of their life cycle.

Wetlands are especially attractive to birders because of the sheer number of birds it is possible to see and hear in a day. Economically, wetlands sustain fisheries, recreation, and tourism worth billions of dollars annually.

Types of Wetlands in North America

The main types of wetlands in North America. These categories, while broad, are based on their dominant vegetation, water source, and soil characteristics. Here’s a brief structured overview of the plants and bird species typically associated with each major wetland type in North America.

Marshes

Marshes are wetlands characterized by herbaceous, non-woody plants like grasses, sedges, and cattails. They are often fed by surface water from rivers, lakes, or runoff, and their soils are typically mineral-rich. Marshes are generally nutrient-rich and support a diverse range of plant and animal life.

Saltmarshes & Tidal Flats

Found along coastlines and estuaries, their water levels fluctuate with the ocean tides. They can be saltwater, brackish, or even freshwater, depending on their location relative to the ocean and freshwater inputs.

Plants

Smooth Cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora)

Saltmeadow Cordgrass (Spartina patens)

Glasswort (Salicornia spp.)

Black Needlerush (Juncus roemerianus)

Sea Lavender (Limonium carolinianum)

Birds

Clapper Rail

Wood Storks and Spoonbills

Egrets and herons

Osprey and Bald Eagle

Ibises, shorebirds, terns and gulls

Some ducks and mergansers

Non-tidal Marshes

Located inland, these are the most common and diverse type wetlands. They form in poorly drained depressions and in the floodplains of lakes and rivers. The productivity depends on the quality of the water input. Non-tidal marshes include Bogs and Fens wetlands, which are fed by rain or ground water and are considered low productivity nutrient-poor wetlands.

Plants

Cattails (Typha spp.)

Bulrushes (Schoenoplectus spp.)

Reeds (Phragmites australis)

Smartweeds (Polygonum spp.)

Arrowheads (Sagittaria spp.)

Water lilies (Nymphaea spp.)

Birds

Rails, Gallinules, Coots

Herons, egrets, and bitterns

Ducks, mergansers, grebes

Cranes

Wood stork and Spoonbills

Red-shouldered hawk, Snail kite and Osprey.

Ibises and Limpkin

Swamps

Swamps are wetlands dominated by woody plants or trees such as cypress, tupelos, and oaks (forested swamps), or dominated by buttonbush and willows (Shrub Swamps). They are primarily fed by surface water and can have standing water for part of the year. The soil in swamps is very wet during the growing season.

Plants

Bald Cypress (Taxodium distichum)

Water Tupelo (Nyssa aquatica)

Red Maple (Acer rubrum)

Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)

Swamp Rose (Rosa palustris)

Birds

Wood Stork and Spoonbill

Limpkin

Egrets and herons

Red-shouldered Hawk and Snail Kite

Rails and gallinules

Cranes

Mangrove Swamps

A type of coastal swamp found in tropical and subtropical regions, like southern Florida, characterized by salt-tolerant mangrove trees.

Plants

Red Mangrove (Rhizophora mangle)

Black Mangrove (Avicennia germinans)

White Mangrove (Laguncularia racemosa)

Buttonwood (Conocarpus erectus)

Birds

Reddish Egret, Yellow-crowned Night-Heron other egrets and herons

White Ibis

Wood Stork and Roseate Spoonbill

Osprey

Cormorants and Anhinga

Terns

Lakes & Ponds

Lakes and ponds are inland depressions that hold standing freshwater. Ponds are generally smaller and shallower, allowing sunlight to penetrate all the way to the bottom. Lakes, on the other hand, are larger and deeper, often with a distinct shoreline. Both are home to a wide variety of aquatic organisms, from microscopic life to fish and amphibians.

Plants

Pondweeds (Potamogeton spp.)

Water lilies (Nymphaea spp.)

Duckweed (Lemna spp.)

Coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum)

Pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata)

Birds

Ducks, Mergansers and Grebes

White Pelican

Cormorants and Anhinga

Gallinules, Coots, and Rails (edges)

Osprey, Snail Kite and Bald Eagle

Belted Kingfisher

Egrets and Herons

Rivers & Streams

Rivers and streams are flowing bodies of freshwater that move in one direction. Streams are smaller and often serve as the headwaters of a river. The constant flow of water in these habitats provides high oxygen levels and transports nutrients and sediment. The organisms that live here are specifically adapted to the continuous current.

Plants

Water willow (Justicia americana)

Pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata)

Arrow arum (Peltandra virginica)

Sedges (Carex spp.)

Rushes (Juncus spp.)

Birds

Belted Kingfisher

Cormorants and Anhinga

Ducks and Mergansers

Herons, Egrets

Osprey and Bald Eagle

Gulls and Terns

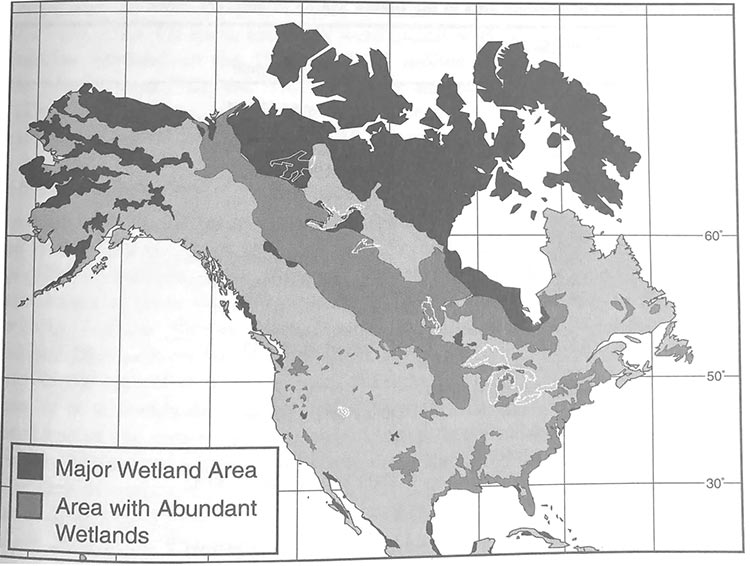

Concentration of Wetlands in North America

The major wetalnd regions of North America are shown in Figure 4-8. Regional diversity and the lack of unanimity abouth the defition of a wetland, as described above, in chapte 2-3make it difficult to inventory the wetland resourve in general. Nevertheless attempts have been make to find out how many wetlands there are in the U.S. ‘

Wetlands have been drained or destroyed historically, especially in the U.S.?

Historically, wetlands have been drained or destroyed through large-scale human interventions aimed at converting them into farmland, urban areas, or industrial zones. In the U.S., this process accelerated during the 19th and 20th centuries with policies and technologies that encouraged land “reclamation.” Early settlers drained wetlands using ditches and wooden sluices, while later developments relied on pumps, levees, and extensive canal systems. One of the largest examples is the drainage of the Florida Everglades, which was transformed for agriculture and development through massive canal construction beginning in the early 1900s.

Nationally, wetland loss has been staggering: by the mid-1980s, over 50% of the original wetlands in the contiguous U.S. had been destroyed, representing more than 100 million acres lost since colonial times. The main drivers were agriculture (responsible for about 87% of wetland losses historically), followed by urban expansion, industrial use, and infrastructure projects such as highways and dams.

Shift in U.S. wetland policies from drainage to conservation

The U.S. shifted from draining to conserving wetlands in the late 20th century as science revealed their vital role in flood control, water purification, and wildlife habitat. The Clean Water Act (1972) and the Swampbuster provision of the 1985 Farm Bill marked turning points, reflecting growing public awareness, recognition of biodiversity loss, and the high economic value of wetland ecosystem services.

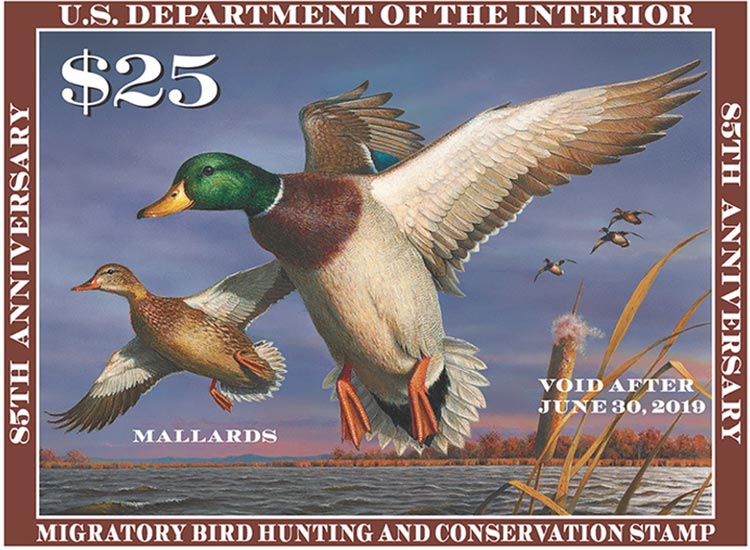

The duck stamp program and its impact in wetland conservation

The Federal Duck Stamp Program, created in 1934, has been one of the most successful conservation initiatives in U.S. history. Waterfowl hunters are required to purchase an annual stamp, and 98 cents of every dollar goes directly to wetland and grassland conservation. Since its inception, the program has raised over $1.2 billion and helped protect or restore more than 6 million acres of habitat across the United States.

These funds are used primarily by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to acquire and manage lands for the National Wildlife Refuge System, ensuring that critical wetland areas remain intact not only for ducks and geese but also for thousands of other species of birds, fish, amphibians, and mammals.

In addition to its financial impact, the Duck Stamp has become a symbol of conservation, engaging hunters, birders, and nature enthusiasts alike in wetland protection.

Final Comments

Wetlands are more than transitional landscapes—they are life-support systems for birds, people, and entire ecosystems. From providing vital stopovers for migratory species to shielding coastal communities from floods, their value cannot be overstated. As you explore the state-specific bird guides, keep in mind that each marsh, swamp, and mangrove is part of a larger continental network of wetlands. Protecting them ensures the survival of countless bird species and safeguards the natural benefits humans rely on every day.