After more than 20 years in the field with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, I’ve worked through multiple identification resources. This guide is a comprehensive synthesis designed to elevate your understanding of North American ducks, as well as Geese and Swans.

I aim to bridge the gap between a field guide and in-depth ecological texts, providing the essential knowledge required for advanced birding, effective conservation work, and ethical resource stewardship.

Who is This Guide For?

- Field Ornithologists and Birders: Those seeking to move beyond primary identification into subtle morphological and behavioral differences.

- Waterfowl Managers and Conservation Professionals: Utilizing this guide as a robust reference for population assessments and complex habitat planning.

- Waterfowlers: Enhancing compliance and connection to the resource through deeper species-specific knowledge and ecological context.

What You Will Learn

- Key characteristics that differentiate duck, geese, and swan species: From simple plumage to understanding subtle distinctions in speculum colors, bill laminations, and foot morphology.

- Understanding the major migratory routes (Flyways): Analyzing how longitudinal flyway dynamics influence population counts, breeding dispersal, and genetic mixing.

- The critical role of habitat in duck populations: Exploring the complexities of wetland composition, moist-soil management, and the ecological correlates of breeding success.

- What You Will Learn

- The Family Anatidae: Ducks, Geese, and Swans

- Subfamily Anatinae

- Diving Ducks (Pochards and Bay Ducks)

- Sea Ducks, Mergansers and Eiders (Mergini)

- Subfamily: Anserinidae, Geese and Swans

- The Swans: Unmistakable Elegance

- Subfamily: Dendrocygninae

- Essential Duck Anatomy for Field Identification

- The Visual Keys: Size, Shape, and Silhouette

- Plumage Cycles: Understanding the Annual Color Changes

- Identifying Ducks in Flight and on the Water

- Deciphering Duck Vocalizations

- The Four Major North American Flyways

- Essential Duck Habitats

- The Annual Migration Cycle

- Current Population Status and Conservation Challenges

- The Role of Conservation Organizations

- Waterfowl Hunting Regulations

Taxonomy and the Fundamentals of Classification

The Family Anatidae: Ducks, Geese, and Swans

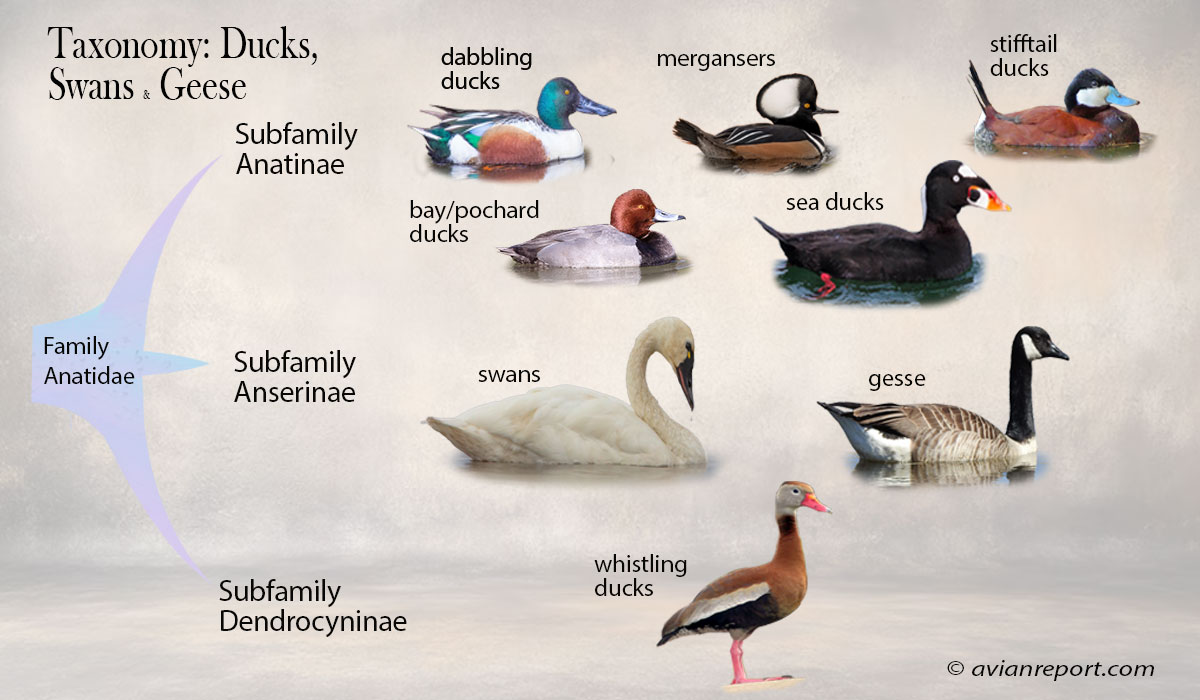

North American waterfowl, including ducks, mergansers, geese, and swans, all belong to the taxonomic family Anatidae. This family is further subdivided into three distinct subfamilies based on their shared evolutionary history, morphology (form), and behavior.

This guide is structured around these three subfamilies, which allows for a logical and systematic examination of the adaptive radiation that has produced the myriad waterfowl forms across North America. The subsequent sections will detail these three subfamilies and the unique species contained within each.

This foundational distinction immediately narrows our scope to the most species-rich and geographically dispersed group, allowing us to examine the adaptive radiation that has produced the varied duck forms across North America.

Profiles of Key North American Species

This is where our taxonomic and anatomical groundwork truly pays off. Moving beyond the generalities of the Dabbler/Diver split, we now focus on the critical species-specific details necessary for rigorous field identification and effective management.

Accurate species-level assessment is paramount for duck population management, as population monitoring, bag limits, and habitat projects hinge on precise identification. We will group species by their ecological tribe, which dictates their life history and conservation needs.

Subfamily Anatinae

Dabbling or Puddle Ducks (Anas, Mareca, Spatula):

Dabbling ducks are the most familiar and most numerous group, defined by their preference for shallow, vegetated wetlands—the marsh edges, flooded fields, and slow-moving river systems. These species are highly responsive to proactive moist-soil management and are of high conservation value, particularly those that breed in the critical Prairie Pothole Region (PPR).

Dabbling Ducks are distinguished by riding high on the water with centralized legs, allowing for vertical takeoff. They exhibit strong sexual dimorphism: bright males and cryptic brown females. Their wide, flat bills are used for surface feeding, or ‘tipping up,’ to consume vegetation and seeds in shallow wetlands. Approximately ten core species regularly occur in North America.

The Iconic Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos)

Though the ubiquitous “Greenhead” drake is unmistakable, identification focus should shift to the subtle distinction of the hen’s bill pattern (orange-yellow with a dark, often mottled saddle) to confirm purity. Hybridization with domestic stock is a growing concern, especially in urban or high-density feeding areas, complicating local population assessments.

Northern Pintail (Anas acuta)

The drake is the epitome of elegance, identified by its slender form and long central tail feathers (pin). The hen presents a major identification challenge; look for the exceptionally long, slender neck, the pale neck stripe, and the subtly shaped, uniform gray bill, which lacks the orange hue found on many Mallard hens. The Pintail’s population success is closely tied to favorable conditions in the PPR.

Teal Species (Green-Winged, Blue-Winged, Cinnamon)

The Green-Winged Teal is our smallest dabbler, identifiable by its rapid, buzzing flight. Blue-Winged and Cinnamon Teal are highly sensitive to hunting seasons due to their late-arrival (spring) and early-departure (fall) migration patterns. Distinguishing the cryptic hens of the latter two often relies on subtle differences in bill size (Blue-Winged generally having a slightly broader bill) and head contour.

American Wigeon and Gadwall

The American Wigeon (Anas americana), often nicknamed “Baldpate” for the drake’s white crown, is a grazing specialist.

The Gadwall (Anas strepera) is frequently overlooked—the “Grey Duck”—but the drake is reliably identified by the prominent black patch on the stern and the unique bright white speculum visible on both sexes, a feature which instantly separates it from most other Anas species in flight.

Species withing the Dabbling Duck (Puddle Duck) Group

Anas

Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos)

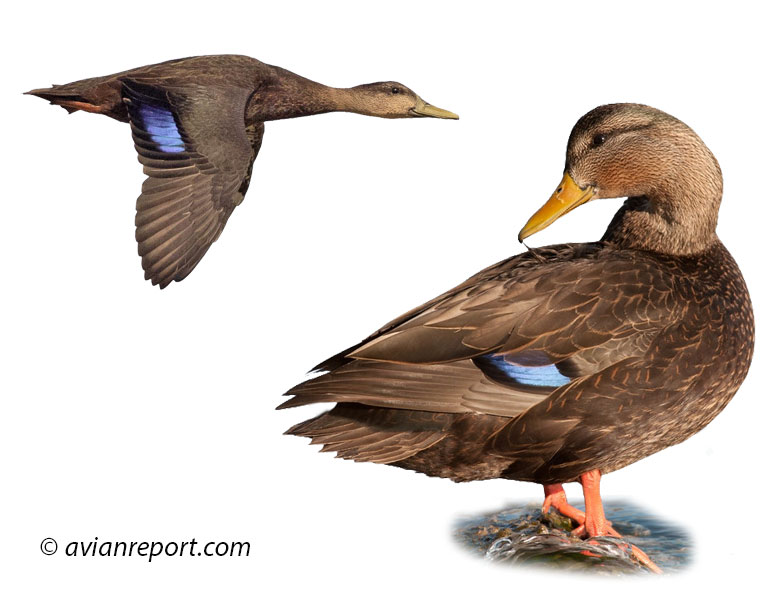

American Black Duck (Anas rubripes)

Mottled Duck (Anas fulvigula)

Mexican Duck (Anas diazi)

Northern Pintail (Anas acuta)

Green-winged Teal (Anas crecca)

Mareca

Gadwall (Mareca strepera)

American Wigeon (Mareca americana)

Eurasian Wigeon (Mareca penelope)

Spatula

Blue-winged Teal (Spatula discors)

Cinnamon Teal (Spatula cyanoptera)

Northern Shoveler (Spatula clypeata)

Wood Duck and Muscovy Duck: The unique Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) and invasive Muscovy Duck (Cairina moschata) are now often grouped here. Both are highly dimorphic but are unique in being able to comfortably perch in trees.

Diving Ducks (Pochards and Bay Ducks)

Pochards and Bay Ducks (Aythya): Pochards and Bay Ducks are the classic Diving Ducks. They have compact, heavy bodies and their legs are set far back, causing them to ride low on the water. They exhibit strong sexual dimorphism—males are patterned, while females are dull brown. Their feeding strategy is full submergence to consume tubers and invertebrates from the bottom of deep lakes and bays. Five core species (genus Aythya), including the Canvasback, Redhead and Scaups

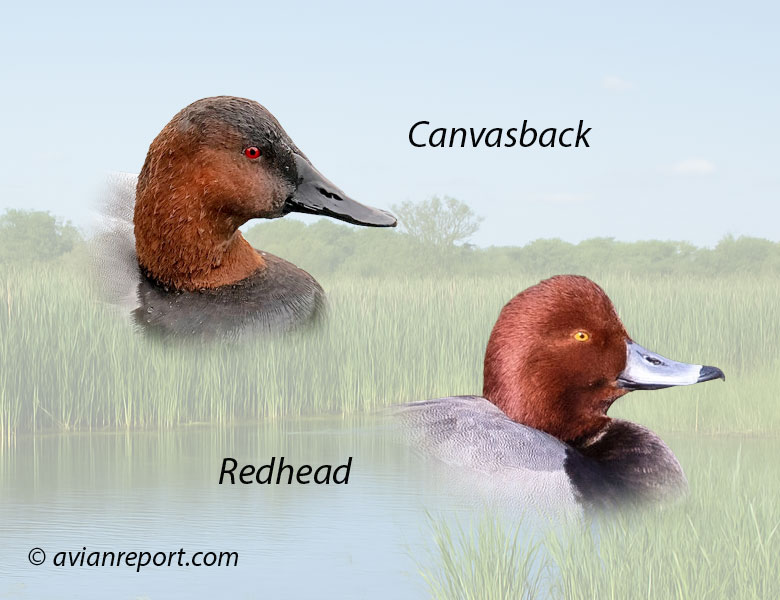

Canvasback (Aythya valisineria) and Redhead (Aythya americana): The flagship species of the genus Aythya. The Canvasback possesses the critical field mark of the long, sloping head and bill profile that separates it from the rounded head of the Redhead. The drake Canvasback is further distinguished by its stark white back, contrasting with the uniform grey-backed Redhead drake. Hens of both species are often reliably separated only by these same crucial head profiles.

Scaup (Greater and Lesser): The notorious “Scaup complex” represents a major identification challenge, especially in the field where the species often co-occur. The most reliable visual differences relate to the head shape and color sheen: the Greater Scaup exhibits a rounded head and a green/glossy sheen; the Lesser Scaup has a more peaked or tufted crown and a purple/glossy sheen.

The wing speculum, however, is the most consistent distinguishing feature: the Greater Scaup’s white secondary feathers extend further into the primary feathers than those of the Lesser Scaup.

Ring-Necked Duck: A black-and-white diver that surprisingly favors smaller, freshwater wetlands, often overlapping with dabbler habitat. The diagnostic feature, often visible even at a distance, is the sharp, white ring encircling the gray-blue bill, while the namesake chestnut neck-ring is virtually impossible to observe in field conditions. The peaked crown also gives the head a distinct, angular profile.

Specie of Pochards and Bay Ducks

Aythya

Canvasback (Aythya valisineria)

Redhead (Aythya americana)

Ring-necked Duck (Aythya collaris)

Greater Scaup (Aythya marila)

Lesser Scaup (Aythya affinis)

Sea Ducks, Mergansers and Eiders (Mergini)

Sea Ducks and Mergansers The term “sea ducks” refers to a collection of species often associated with coastal waters and large, deep freshwater lakes: eiders, scoters, goldeneyes, the Bufflehead, the Harlequin Duck, and the Long-tailed Duck.

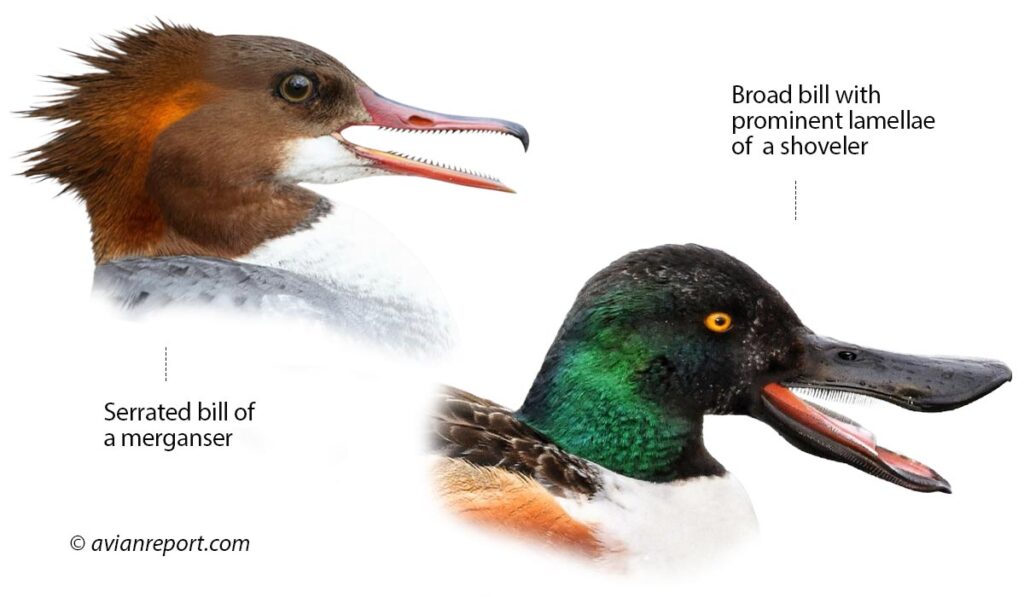

They are compact and heavy-bodied with strong sexual dimorphism. They feed by diving for mollusks and crustaceans (e.g., Scoters, Eiders) or invertebrates and plant matter (e.g., Goldeneyes, Bufflehead). Mergansers engage in underwater pursuit possessing thin, serrated bills (sawbills) for catching fish.

Specialized Feeding and Coastal Habitats:

These species rely heavily on marine invertebrates, crustaceans, and fish, often inhabiting cold, turbulent water.

Common and King Eiders:

Large, heavy-bodied divers adapted to the arctic and sub-arctic coasts. The drake Common Eider is characterized by its white back and the unique green nape and black cap extending into a frontal lobe on the bill.

The King Eider drake has a massive, colorful orange frontal shield. Due to their coastal concentration, these species are particularly vulnerable to oil spills and marine habitat disruption.

Scoters (Black, Surf, White-Winged):

These robust ducks are coastal specialists. Drakes are typically all black with white wing patches (White-Winged) or flashes of color on the bill (Surf). The hens are a cryptic, uniform brown, requiring close observation of facial markings—for example, the pale face patches on the Surf Scoter hen. They are distinguished in flight by their deep, heavy wingbeats and low, wave-following path.

Mergansers (Common, Red-Breasted, Hooded):

The “sawbills” are specialized fish-eaters. Their long, thin bills are equipped with serrated edges, perfectly adapted for grasping and retaining slippery aquatic prey.

Identification is straightforward: Common Merganser (sleek, bottle-green head), Red-Breasted Merganser (shaggy crest), and Hooded Merganser (small and fantastically crested).

Bufflehead and Goldeneye:

Small, flashy divers that are also cavity nesters. The Bufflehead is our smallest diver, recognizable by the drake’s large, puffy white head patch.

Goldeneyes (Common and Barrow’s) are identifiable by the distinctive head patch below the eye: the Common has a round white spot, while the less common Barrow’s Goldeneye has a crescent-shaped white spot.

Species of Sea Ducks and Mergansers and Eiders

Somateria

King Eider (Somateria spectabilis)

Common Eider (Somateria mollissima)

Spectacled Eider (Somateria fischeri)

Steller’s Eider (Polysticta stelleri)

Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus)

Long-tailed Duck (Clangula hyemalis)

Melanitta

Surf Scoter (Melanitta perspicillata)

White-winged Scoter (Melanitta deglandi)

Black Scoter (Melanitta americana)

Mergus

Common Merganser (Mergus merganser)

Red-breasted Merganser (Mergus serrator)

Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus)

Bucephala

Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola)

Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula)

Barrow’s Goldeneye (Bucephala islandica)

Stifftail Ducks (Oxyura)

Stifftail Ducks are small, compact, heavy-bodied divers defined by their stiff, spiky tail feathers, which they often hold cocked upright. They exhibit pronounced sexual dimorphism, with males showing brilliant colors (rust-red body) during breeding season. Stifftails are highly aquatic, rarely leaving the water, and feed by deep diving for insect larvae and seeds. Only one species, the widespread Ruddy Duck, regularly occurs in North America.

Subfamily: Anserinidae, Geese and Swans

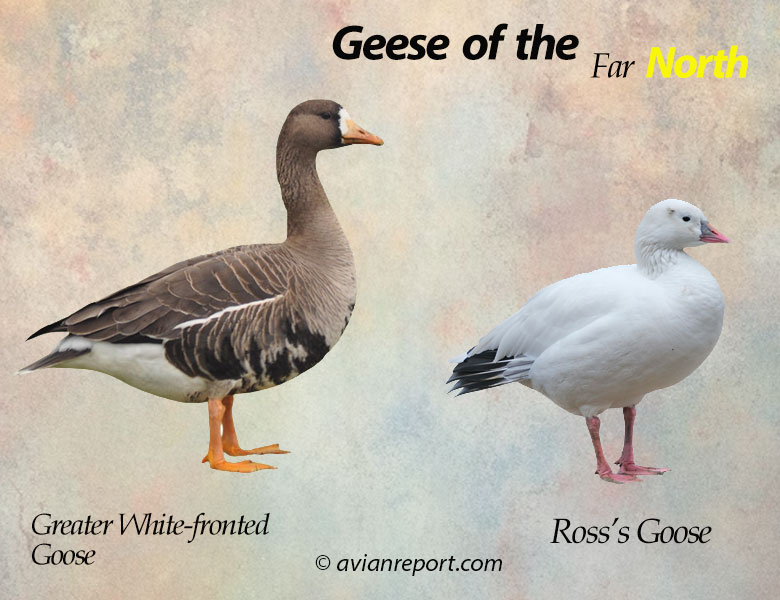

Geese (Anser, Branta, Chen) are the large, familiar waterfowl known for their robust, heavy bodies and long necks. They display virtually no sexual dimorphism; males and females look identical, sharing bold white, black, and gray patterns. Geese are predominately terrestrial grazers, feeding heavily on grasses, sedges, and grains, and can spend considerable time out of the water. They are typically found in large, organized flocks during migration. Nine species regularly occur in North America.

Key ID and Structure: Geese are characterized by their uniformly colored plumage (often lacking the striking sexual dimorphism of ducks), greater body mass, longer legs, and longer necks. They walk with ease and feed primarily on grasses, grains, and agricultural waste.

Management Relevance: Population dynamics are often linked to agricultural practices and urban habitat, requiring different regulatory strategies than those applied to wetland-dependent ducks.

Species of Geese

Anser

Emperor Goose (Anser canagicus)

Snow Goose (Anser caerulescens)

Ross’s Goose (Anser rossii)

Greater White-fronted Goose (Anser albifrons)

Graylag Goose (Anser anser)

Branta

Brant (Branta bernicla)

Canada Goose (Branta canadensis)

Barnacle Goose (Branta leucopsis)

The Swans: Unmistakable Elegance

Swans (Cygnus) are the largest and most massive waterfowl, instantly recognizable by their pure white plumage. They are monomorphic, with virtually no sexual dimorphism in coloration. Swans are primarily aquatic grazers, using their exceptionally long necks to reach submerged aquatic vegetation and roots. Their long necks and huge wingspans require large, clear areas for takeoff. Only three species—Tundra, Trumpeter, and the non-native Mute Swan—regularly occur in North America.

- Key ID and Status: Their massive size, all-white plumage (except the Mute Swan’s orange bill), and graceful, elongated necks make them unmistakable. Identification among the three species hinges on bill morphology and neck posture.

- Conservation Status: The native Trumpeter Swan is a prime restoration success story, requiring careful population monitoring to ensure sustained recovery and differentiate it from the smaller, more numerous Tundra Swan.

Functional Comparison: Grazers vs. Divers/Filterers

The key functional difference is their dependency on water:

- Anatinae (Ducks): Highly aquatic, relying on water for food (diving, filtering) and immediate escape.

- Anserinae (Geese and Swans): Highly adaptable, spending considerable time out of the water grazing, a strategy that often allows them to utilize managed agricultural lands and bypass traditional wetland constraints.

Species of Swans

Cygnus

Tundra Swan (Cygnus columbianus)

Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus buccinator)

Mute Swan (Cygnus olor)

Subfamily: Dendrocygninae

Whistling: Ducks (Dendrocygna): are distinctive waterfowl, recognized by their long legs and upright posture. Both males and females exhibit monomorphic plumage, sharing similar, striking patterns. They are primarily grazers, feeding on seeds and vegetation both on land and in shallow water, a behavior more akin to geese than to diving or dabbling ducks. Their name comes from their clear, three-syllable whistling call. Only two species, the Black-bellied and the Fulvous Whistling Ducks, regularly occur in North America.

The Big Divide: Dabbling Ducks vs. Diving Ducks (Puddle vs. Bay)

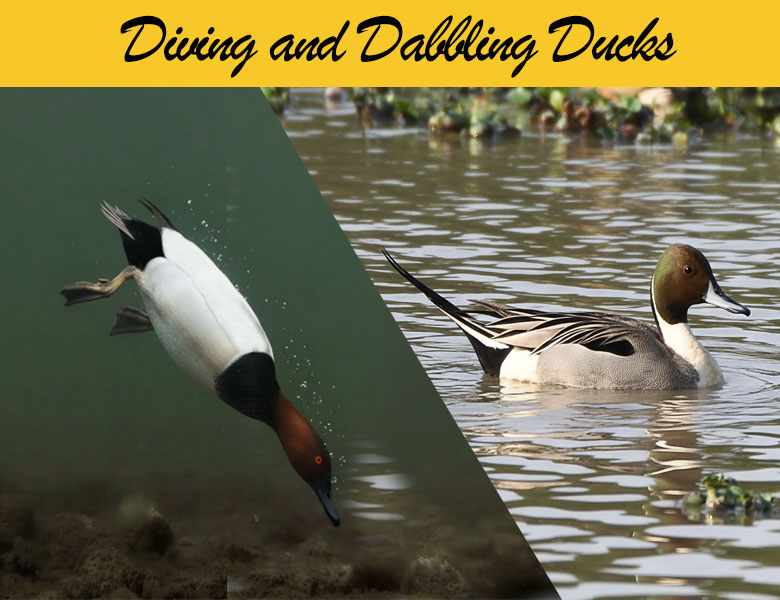

This primary dichotomy is the cornerstone of waterfowl classification, reflecting a critical evolutionary and ecological divergence. The division between Dabbling Ducks (Tribe Anatini, or Puddle Ducks) and Diving Ducks (Tribes Aythyini and Mergini, or Bay Ducks) is fundamental to identification and habitat ecology, driven almost entirely by feeding strategy.

Feeding Behavior (Tipping vs. Submerging): Dabblers feed predominantly by surface-skimming or tipping, accessing shallow aquatic vegetation and invertebrates without fully submerging their bodies. This confines them to shallow lentic or lotic systems. Divers, conversely, obtain food by submerging completely, often reaching significant depths for mollusks, fish, or benthic vegetation.

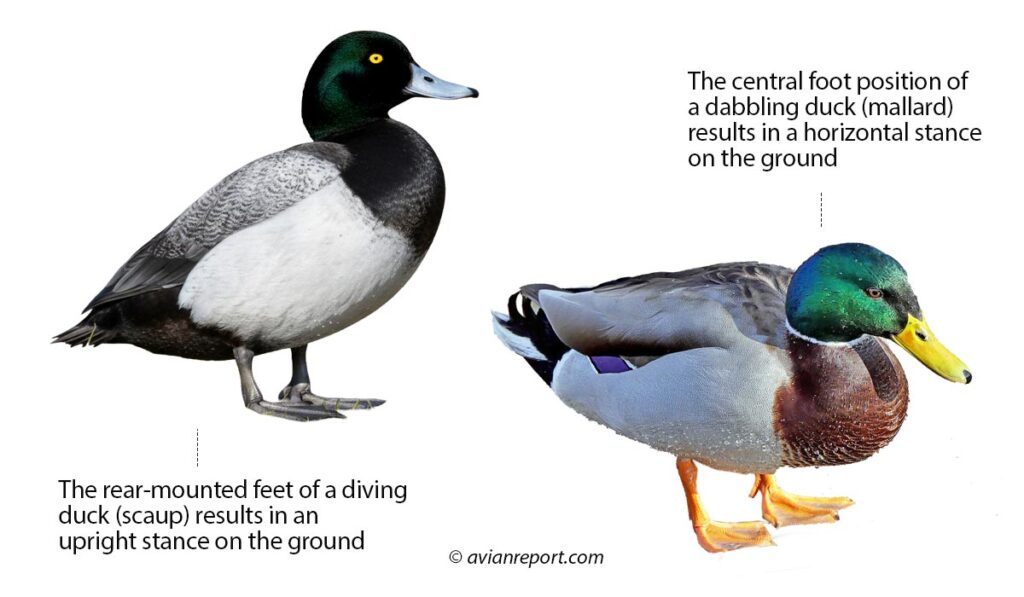

- Body Shape and Takeoff Style (Springing vs. Pattering): The divergence in body plan is linked directly to mobility. Dabblers feature legs positioned closer to the center of their mass, allowing for relatively agile walking and a rapid, vertical, “springing” takeoff directly into the air.

Divers, however, have legs positioned farther back on the body, optimizing propulsion for deep-water diving. This posterior leg placement necessitates a characteristic “pattering” run across the water surface for several meters before achieving lift-off, and results in a notably clumsy gait on land.

Essential Duck Anatomy for Field Identification

Field identification often relies on fine-scale morphological cues that demand familiarity with specialized anatomical markers.

The Speculum (The key wing patch color): The speculum is a patch of often iridescent, brightly colored secondary flight feathers. In Dabbling Ducks, this patch is typically vivid (e.g., the Mallard’s iridescent blue, often bordered by white bars), serving as a crucial mark in flight. Diving Ducks generally possess duller, less contrasting specula, or may lack them entirely.

Bill Structure and Function (Filter feeding vs. grasping): The duck bill is highly specialized, containing lamellae—fine, comb-like structures used for filtering food. The degree of lamellar development is key: filter-feeders like the Northern Shoveler have highly developed, dense lamellae for straining plankton, while piscivorous species, like Mergansers, possess a serrated, or “saw-toothed,” bill adapted for grasping and retaining slippery prey.

Foot Placement (Center vs. rear-mounted for walking/diving): This feature is the anatomical consequence of the Dabbler/Diver split. The central foot position of dabblers provides balance for walking and vertical takeoff, while the rear-mounted, larger feet of divers maximize thrust for sub-surface locomotion..

Dive Deeper into the Core Concepts: See our dedicated guide, Dabbling Ducks vs. Diving Ducks: The Key Differences in North American Waterfowl.

Mastering Duck Identification Techniques

The ability to accurately identify ducks, especially the cryptic hen plumages, hinges on moving beyond simple color patterns and utilizing the totality of the bird’s presentation—its movement, profile, and voice.

When conducting waterfowl surveys or making rapid, in-the-field calls, these comprehensive techniques are indispensable.

The Visual Keys: Size, Shape, and Silhouette

- Head Shape and Profile (e.g., the slopping forehead of the Canvasback): The subtle slope and contour of the head, neck, and bill junction can be more reliable than color, particularly at long distances or in poor light. For instance, the Canvasback exhibits a distinct, long, sloping profile where the head flows seamlessly into the bill, a trait instantly separating it from the rounded head of the similar Redhead.

Similarly, the relatively small, high-domed head of the Greater Scaup contrasts with the more peaked, often tufted look of the Lesser Scaup. - Neck Length and Position in the Water (e.g., Pintail vs. Wigeon): The proportion of the bird that sits above the waterline is highly informative. Dabblers, being more buoyant, tend to ride higher.

- The Northern Pintail stands out due to its extremely long, slender neck, giving it an elegant, almost swan-like profile. Conversely, the smaller, compact diving ducks like the Bufflehead sit low, often appearing as little more than a brightly colored head and stern above the water surface, a direct result of their diving optimization.

Plumage Cycles: Understanding the Annual Color Changes

The annual molt cycle in ducks presents significant identification challenges, especially for male (drake) birds.

- The Bright Breeding/Nuptial Plumage (Drakes in Winter/Spring): This is the familiar, colorful plumage that drakes acquire leading up to and during the spring breeding season. It is specifically evolved for attracting a mate and is the easiest plumage state for species-level identification (e.g., the shimmering green head of the Mallard, the rusty chestnut of the Redhead).

- The Hen-like Eclipse Plumage (Drakes in Summer/Fall): Following the breeding season, drakes undergo a rapid post-nuptial molt and enter the cryptic eclipse plumage. During this period, which lasts through early autumn, drakes strongly resemble hens of their own species.

Since they are flightless for a short time during this complete wing molt, this dull, camouflage-heavy plumage offers protective coloration. Accurate identification during the eclipse phase relies heavily on size, shape, bill color, and behavioral cues rather than head color or speculum.

Identifying Ducks in Flight and on the Water

Dynamic characteristics—how a bird moves—are often the best differentiating factors in a mixed flock or when working large bodies of water.

- Wingbeat Speed and Pattern: Smaller ducks, such as the various Teal species and the Bufflehead, exhibit a noticeably rapid, buzzing wingbeat that distinguishes them from the slower, deeper wingstrokes of larger species like the Mallard or Northern Shoveler. In mixed flocks, this frequency difference can be used as an immediate sorting mechanism.

- Flocking Behavior and Formation (Loose groups vs. tight bunches): Flock behavior is tied to species ecology. Diving ducks, particularly Scaup and Canvasbacks, often form dense, tightly clustered rafts on the water and fly in tight, fast-moving bunches in the air. Dabbling ducks, in contrast, typically fly in looser, more erratic formations.

- Flight Silhouettes (Long-necked, long-tailed, etc.): When viewed against the sky, the bird’s overall outline is diagnostic. The long, tapered tail of the Northern Pintail is instantly recognizable, as is the heavy, large-billed profile of the Northern Shoveler in flight. Sea ducks, like the Scoters, appear heavy-bodied and fly with a deliberate, sometimes undulating motion.

Deciphering Duck Vocalizations

Auditory identification is an overlooked but essential skill for waterfowl work, especially in dense marsh cover or low light conditions.

- Common Quacks (Hens) vs. Whistles, Grunts, and Squeals (Drakes): It is a common misconception that all ducks “quack.” The loud, resonant quack is predominantly produced by Mallard hens and a few related Anas species. Most drakes of diving and specialized species are silent or produce highly specific non-quacking calls: the Wigeon drake whistles (“whee-whee-whoo“), the Wood Duck drake makes a rising, peeping call, and Goldeneyes produce deep, rattling sounds in courtship. Recognizing these sex- and species-specific calls is crucial for confirmation when visual cues are ambiguous.

Habitat, Migration, and the Waterfowl Flyways

From a resource management standpoint, understanding the link between habitat, migratory routes, and population dynamics is non-negotiable. Duck management is inherently continental, requiring us to look beyond local conservation efforts to the four major migratory systems that govern the movement of nearly all North American waterfowl.

The Four Major North American Flyways

The Flyway system is the operational framework for managing migratory bird populations, established through international agreement and executed via four regional committees. This cooperative structure allows for science-based regulation (such as setting species-specific bag limits) that adapts to real-time population data across the continent.

- Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific Flyways: These four main corridors extend from the boreal breeding grounds of Canada and Alaska down to the wintering areas in the southern U.S., Mexico, and the Caribbean. While the paths are generalized, they provide the regulatory basis for assessing population health and harvest limits by region.

- Key Bottlenecks and Stopover Points: Critical to our work are the areas where high numbers of migrants converge. These include the Great Salt Lake, the central Nebraska Platte River, and the Louisiana coastal marshes. These areas act as essential “refueling stations” (stopover habitat) where birds must rapidly acquire energy reserves. Habitat loss or degradation in these critical bottlenecks poses a disproportionately high risk to the entire flyway population and can increase the risk of disease transmission, such as Avian Influenza.

Essential Duck Habitats

Duck habitats are as diverse as the species themselves, but we can categorize them by their critical function during the breeding, migration, or wintering phases. Matching species needs to habitat availability is the core of effective habitat management.

- Freshwater Marshes and Wetlands (Moist-Soil Management): This is the domain of the dabbling ducks, particularly the Prairie Pothole Region (PPR) which is known as North America’s “Duck Factory.” Moist-soil management is a specialized technique we employ, involving controlled dewatering (drawdowns) to promote the growth of highly productive annual plants (like smartweed, wild millet, and barnyard grass). These plants produce millions of high-energy seeds, providing the caloric subsidy required for pre-migration staging.

- Coastal Bays and Estuaries: These large, deep, often brackish or saltwater habitats are essential for diving ducks and all sea duck species, especially during the non-breeding season. Their diet relies heavily on Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV), like eelgrass (Zostera), and benthic invertebrates (mollusks, crustaceans). The health of these coastal ecosystems is severely threatened by coastal development and nutrient runoff, which degrades water clarity necessary for SAV growth.

- Timber and Forested Areas (Crucial for Wood Ducks): This highlights the importance of riparian wetlands and mature forests. The Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) and the Hooded Merganser are primary cavity nesters, relying on natural tree hollows or managed nest boxes. The presence of suitable, dense cover surrounding the water is also vital for brood rearing, offering protection from terrestrial predators.

The Annual Migration Cycle

The annual cycle is a grueling sequence of molts, long-distance movements, and reproductive effort, all driven by instinct and environmental cues.

- Fall Migration: Timing and Cold Front Triggers: The southbound migration is primarily triggered by decreasing photoperiod (day length) and, critically, by the passage of strong, continental cold fronts. These fronts bring favorable tailwinds and the threat of freezing water, which immediately pushes ducks, especially the less cold-tolerant species like Blue-Winged Teal, further south in large waves.

- Spring Migration: Return to Breeding Grounds: The northbound journey is dictated by the urgent need to occupy the best breeding territories, particularly in the PPR. Ducks must arrive as soon as the ice melts (pairing often occurs on the wintering grounds or during this return journey) to maximize the short breeding window. The timing is critical and often carries high energetic costs, depending on weather and habitat conditions encountered along the way.

Conservation, Health, and Regulations

This final section addresses the critical management and policy infrastructure that enables the continued sustainability of North America’s waterfowl populations. The work of the USFWS revolves around continuous monitoring, scientific modeling, and partnership coordination to ensure these magnificent resources remain viable for future generations.

Current Population Status and Conservation Challenges

Accurate population assessment is the foundation of Adaptive Harvest Management (AHM).

- Monitoring and Research (Banding and Surveys): Population metrics are primarily derived from the annual Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey (BWPHS), which covers the major nesting areas. This count, however, is supplemented by banding data. The recovery rate of individually marked birds provides crucial estimates of annual survival and harvest rates—data points essential for modeling population dynamics, often expressed using the Lincoln-Petersen estimator to approximate population size based on recapture rates.

- Major Threats (Habitat Loss, Climate Change, Disease): The greatest current threats are landscape-scale:

- Habitat Loss: The continual conversion and drainage of wetlands in the Prairie Pothole Region remains the single largest threat to dabbling duck production.

- Climate Change: Increased frequency and severity of droughts in the western breeding areas destabilize the critical wetland conditions needed for successful nesting and brood rearing.

- Disease: Outbreaks of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) and endemic threats like Avian Botulism (Type C/E), often triggered by warm-water conditions and mass die-offs, require constant surveillance to prevent massive population impacts.

The Role of Conservation Organizations

The USFWS and state agencies rely on robust public and private partnerships, both for funding and on-the-ground project execution.

- Funding Wetland Protection (e.g., Duck Stamp Program): Since its inception in 1934, the Federal Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp (Duck Stamp) has been a monumental success. Nearly 98% of the purchase price goes directly toward acquiring or leasing wetland habitat for the National Wildlife Refuge System. This single program is the primary funding engine for waterfowl conservation land acquisition.

- Continental Strategy (North American Waterfowl Management Plan – NAWMP): This plan, signed by the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, sets the population goals and habitat conservation targets across the continent. It provides the essential, unified vision that guides the work of all partners, including non-governmental organizations like Ducks Unlimited and The Nature Conservancy.

Waterfowl Hunting Regulations

Regulations are the legal and science-based mechanism used to sustain populations while allowing recreational use.

- Understanding Species-Specific Bag Limits: Bag limits and season lengths are not arbitrary; they are determined annually through a rigorous, mathematical process called Adaptive Harvest Management (AHM). AHM uses the current population data (BWPHS) and harvest estimates (banding) to model the optimal regulatory strategy (liberal, moderate, restrictive) for each species based on its predicted response to hunting pressure. This allows for fine-tuning regulations for vulnerable species (like certain Sea Ducks) while maximizing opportunity for abundant species (like Mallards).

- Safety and Ethical Hunting Practices: The ethical component is inseparable from the science. This includes being a proficient identifier (critical to avoiding accidental take of protected or low-population species), respecting local and federal regulations, and ensuring the swift and humane retrieval of harvested birds. Compliance and responsible stewardship by the hunting community are essential inputs to the overall conservation feedback loop.

Conclusion:

The true value of this guide isn’t just the ability to identify a rare hen in the field, but the understanding that conservation success hinges on precisely that level of detail. By synthesizing field identification skills with ecological knowledge and conservation policy, you have moved from observer to steward of this magnificent natural resource. This resource depends entirely on the dedication of people like you—those who understand the big picture.

The goal of this guide was always to provide you with the professional-grade context necessary for genuine resource stewardship. I hope this document serves as a strong foundation for your future work and study. Please let me know if you’d like me to expand any of the internal links.