The family Ardeidae contains some of North America’s most captivating wading birds: herons, egrets, and bitterns. Scientifically, herons and egrets are closely related. This ancient family, which has been wading through wetlands for millions of years, shares unique traits, including the S-shaped neck used for lightning-speed strikes and powder down for cleaning. Since they sit at the top of the food chain, herons are vital biological indicators of wetland health. Explore identification, behavior, and the conservation history of Herons, Egrets, and Bitterns.

1. What are Herons, Egrets, and Bitterns?

Scientifically, there is little biological difference between a “heron” and an “egret.” Both belong to the family Ardeidae, which also includes bitterns and night-herons.

- Herons: Generally refers to the larger, longer-billed species with darker or mixed coloration (e.g., Great Blue Heron).

- Egrets: Historically used to describe white herons that develop elaborate “aigrettes” (plumes) during the breeding season.

- Bitterns: The solitary, camouflaged introverts of the family. They are shorter-necked and renowned for their ability to blend into dense reed beds.

Taxonomy and Evolution

The evolutionary history of this family is ancient, extending back to the Early Oligocene epoch (32–30 million years ago). Fossil records, such as the early heron found in Belgium, indicate that these birds have been wading through Earth’s wetlands for millions of years.

The following is a brief profile of North American species divided into three main subfamilies:

The Herons & Egrets (Ardeinae): The typical herons and egrets.

- Great Blue Heron: The largest and most widespread. Look for the slate-gray body and black plume on the head.

- Great Egret: The symbol of the Audubon Society. Tall, white, with black legs and a yellow bill.

- Snowy Egret: Smaller than the Great. Look for the “Golden Slippers” (yellow feet) and black bill.

- Green Heron: Small, stocky, and intelligent. Often found crouching on logs at the water’s edge.

- Little Blue Heron: Unique because juveniles are white, while adults are slate-blue.

- Tricolored Heron: Formerly the “Louisiana Heron.” Distinctive white belly and active hunting style.

- Reddish Egret: The “dancer” of the flats. Look for the shaggy neck feathers and erratic running behavior.

- Cattle Egret: Often found in fields rather than water, following livestock to catch stirred-up insects.

Night-Herons (Nycticoracinae): The night-herons (stockier, nocturnal).

- Black-crowned Night-Heron: Stocky, red-eyed, and nocturnal.

- Yellow-crowned Night-Heron: A crustacean specialist with a creamy yellow crown.

The Bitterns (Botaurinae): The bitterns (cryptic, solitary).

- American Bittern: Known for its camouflage and booming “water-pump” call.

- Least Bittern: One of the smallest herons, notoriously difficult to spot in dense reeds.

2. Identification: How to Spot an Ardeid

While plumage varies wildly—from the slate-blue of the Great Blue Heron to the snowy white of the Great Egret—all members of this family share unique physical adaptations.

The S-Shaped Neck

Unlike cranes or storks, which fly with their necks outstretched, herons fly with their necks retracted in a tight “S” shape. This is made possible by a modification in their 20 or 21 cervical vertebrae.

- Why do they do this? The anatomy of the neck creates a coil more exaggerated than a simple curve. This acts like a spring, allowing the bird to strike at prey with lightning speed.

- Protection: The esophagus and trachea cross behind the vertebrae in the lower neck, protecting these vital organs when the bird plunges its head forward to strike.

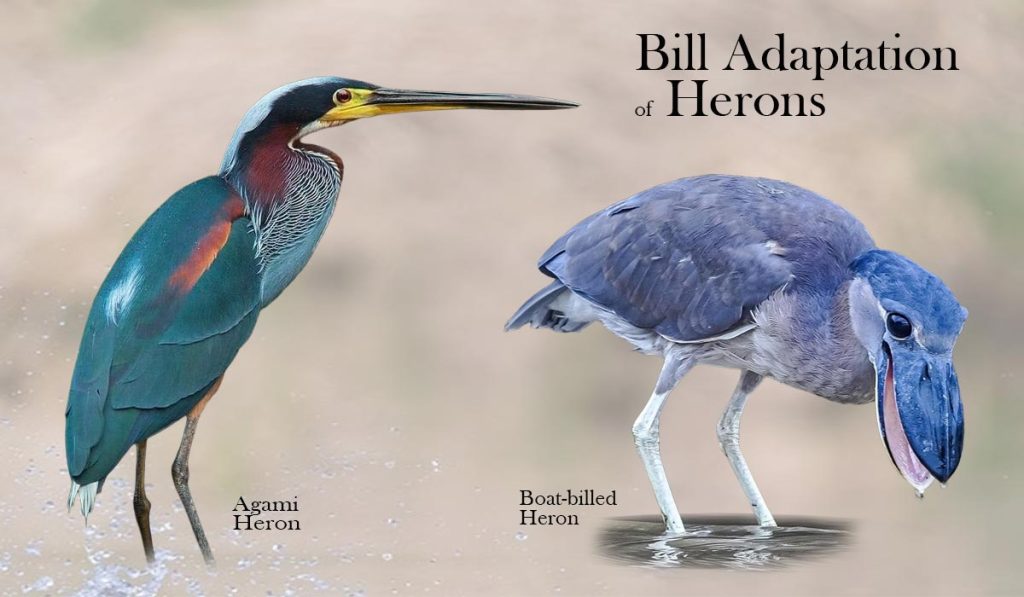

The “Harpoon” Bill

Most species possess long, dagger-like bills adapted for spearing or grasping.

- Narrow Bills: (e.g., Agami Heron) for precision striking.

- Thick Bills: (e.g., Boat-billed Heron) for specialized diets.

- Pectinate Toes: All herons have a “comb-like” middle toe used for preening.

Powder Down

Herons are one of the few bird groups that possess powder down. These specialized feathers on the breast and rump disintegrate into a fine powder, which the birds use to clean fish slime and oils off their plumage.

White Egrets and Herons

White egrets and herons can be confusing because they share many similar physical traits like long necks, white plumage, and long legs, and also because “egret” is a term for some heron species that have white plumage or breeding plumes. Key differences are subtle, including size, leg color, bill shape, and the specific “white morph” of some herons, which is larger with black legs compared to the similar-sized Great Egret’s black legs.

Confused by a white egret or heron? Read our guide: North American White Egrets and Herons: An Identification Guide.

3. Behavior and Ecology

Diet and Hunting: More Than Just Fish

Herons are strictly carnivorous. While they are famous for eating fish, they are opportunistic generalists. Their diet includes crustaceans, amphibians, reptiles, small mammals (like voles), and even other birds (like rails).

The video shows a Reddish Egret performing the strategy of active hunting. The bird runs, spins, and spread its wings to create a “canopy” of shade. This reduces glare on the water and attracts fish seeking cover.

Hunting Techniques:

- Stand and Wait: The most common method. The heron stands motionless, sometimes for hours, waiting for prey to swim within striking distance.

- Canopy Feeding: Some species, like the Reddish Egret, are active hunters. They may run, spin, and spread their wings to create a “canopy” of shade. This reduces glare on the water and attracts fish seeking cover.

- Baiting: The Green Heron is one of the few tool-using animals on earth. It has been documented dropping insects, twigs, or even popcorn onto the water’s surface to lure fish.

Breeding and Nesting: The Rookery

Most herons and egrets are colonial nesters. They gather in large groups known as rookeries, often in mixed-species colonies that can number in the hundreds or thousands.

- Nests: Usually platform sticks built high in trees or on islands (to avoid mammalian predators).

- Siblicide: Hatching is often asynchronous (eggs hatch days apart). In years with scarce food, the older, larger chicks may outcompete or kill the younger siblings.

- Displays: During breeding season, lores (skin near the eye) may turn vivid colors (cherry red in Snowy Egrets). Males perform elaborate “stretch” and “snap” displays to attract mates.

4. Conservation Status

Herons are excellent biological indicators of wetland health. Because they sit at the top of the food chain, they are sensitive to toxins and habitat loss.

Historical Struggle: In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, herons—particularly the Great and Snowy Egrets—were decimated by plume hunters who sought their breeding feathers for the fashion industry. This slaughter sparked the creation of the National Audubon Society and led to early protective legislation.

Modern Threats: While populations rebounded after the plume trade ended, they faced new threats from DDT (which caused eggshell thinning) in the mid-20th century. Today, the primary threats are:

- Habitat Destruction: The draining of wetlands for urbanization and agriculture.

- Climate Change: Changing water regimes and increased hurricane intensity, which can wipe out island rookeries.

Herons have captured human imagination for centuries. In Buddhism, the heron symbolizes purity and the wisdom of stillness. In many Native American cultures, they represent self-reliance and balance. Their ability to stand motionless and strike with precision makes them a powerful symbol of patience.

Explore by State

Ready to find these birds near you? Select your state below to see detailed species accounts, local hotspots, and custom identification plates.

LINKS FORTHCOMING