The conservation status of North American ducks, geese, and swans is highly varied. North American waterfowl encompass some of the continent’s most abundant bird populations alongside species designated as critically declining. Conservation assessments often rely on the Partners in Flight Continental Concern Score (CCS) and data derived from the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS). While many populations are flourishing or stable due to targeted conservation efforts, several species face severe cumulative declines driven by habitat loss, contaminants, and specific regional threats such as hybridization.

Stable and Increasing Populations

The majority of waterfowl species are currently rated as being of low conservation concern, often scoring below 10 out of 20 on the Continental Concern Score (CCS).

Dramatically Increasing Species: Several geese and ducks have seen remarkable population growth in recent decades:

- Canada Goose (Branta canadensis): This ubiquitous species has experienced a dramatic increase of over 7% per year between 1966 and 2019. Partners in Flight estimates the global breeding population at 7.1 million individuals, ranking them at the lowest end of the concern scale (CCS 5/20).

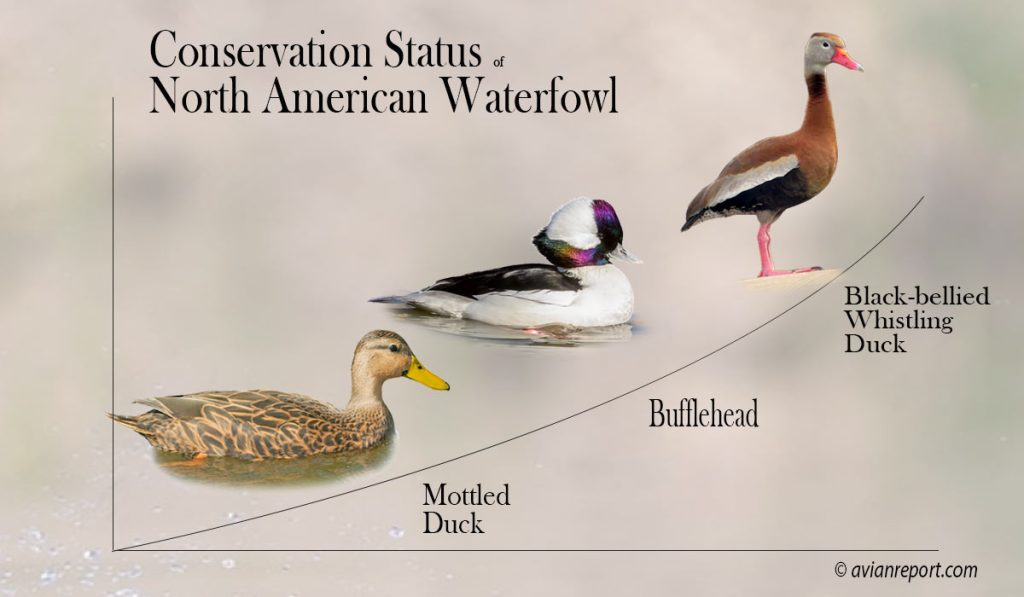

Approximately 2.6 million Canada Geese are harvested annually by hunters, which does not appear to affect their numbers. - Black-bellied Whistling-Duck (Dendrocygna autumnalis): This species has seen its population increase dramatically by approximately 6% per year from 1966–2019. Their global breeding population is estimated at 1 million (CCS 8/20).

- Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus): Populations have increased dramatically by approximately 5% per year between 1966 and 2019. The global breeding population is estimated at 1.1 million (CCS 8/20).

Abundant and Stable Species: The most numerous duck species, the Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), remains a species of low conservation concern (CCS 7/20). It is the most widespread and abundant duck in North America, with the North American population estimated at around 19 million breeding birds. Mallards are the most heavily hunted North American duck, accounting for about 1 of every 3 ducks shot.

Other species showing stable or increasing populations between 1966 and 2019 include:

- Northern Shoveler (Spatula clypeata): Population trend is stable, with an estimated global breeding population of 5.9 million (CCS 7/20). Hunters shot between 450,000 and 470,000 per year from 2019 to 2021.

- Blue-winged Teal (Spatula discors): This is the second most abundant duck in North America, with a stable population trend and a global breeding estimate of 7.8 million (CCS 7/20).

- Gadwall (Mareca strepera): Populations increased by about 1.7% per year between 1966 and 2019, reaching a global breeding population of 4.4 million (CCS 8/20). The Gadwall is the third most hunted duck, with approximately 1.25 million harvested in 2020.

- Ruddy Duck (Oxyura jamaicensis): Populations were stable from 1966 to 2019, with an estimated global breeding population of 1.3 million (CCS 8/20).

- Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola): Populations increased steadily by over 3% per year between 1966 and 2019, reaching a global breeding population of 1.3 million (CCS 8/20).

Species in Steep Decline and Alert Status

A significant segment of North American waterfowl is experiencing cumulative declines, leading to “Tipping Point” designations by conservation groups. These categories indicate a loss of more than 50% of the population in the past 50 years.

Red Alert Species (Perilously Low or Steep Declining Trends):

Three high-Arctic/Gulf Coast species exhibit the most serious decline status:

- Mottled Duck (Anas fulvigula): Listed as a Red Alert Tipping Point species. It experienced a cumulative decline of 72% between 1966 and 2023, equating to an estimated decline of 2.2% per year. Its global breeding population is estimated at >180,000 (CCS 17/20). Hybridization with introduced Mallards is a primary threat, with an estimated 10% of the Florida population having Mallard genetic material.

- Spectacled Eider (Somateria fischeri): Listed as a Red Alert Tipping Point species and categorized as Threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act since 1993. It has the highest possible concern score (CCS 19/20). The global breeding population is estimated at 250,000 individuals.

- Steller’s Eider (Polysticta stelleri): Also listed as a Red Alert Tipping Point species (CCS 19/20). Its global breeding population is estimated at 200,000 individuals.

Orange Alert Species (Accelerated Declines in the Past Decade):

Two arctic sea duck species are in this category:

- King Eider (Somateria spectabilis): Listed as an Orange Alert Tipping Point species (CCS 15/20). This species is still heavily hunted, with tens of thousands taken per year in Canada, Alaska, and Russia. The global breeding population is estimated at >830,000.

- Long-tailed Duck (Clangula hyemalis): Listed as an Orange Alert Tipping Point species (CCS 13/20). The primary conservation concerns are currently unclear, though entanglement in fishing nets historically killed tens of thousands in the 1950s.

Yellow Alert Species (Declining but Stable Recent Trends):

Several ducks and geese have suffered major long-term losses:

- Northern Pintail (Anas acuta): Listed as a Yellow Alert Tipping Point species. It experienced a cumulative decline of 73% between 1966 and 2023 (estimated decline of 2.2% per year). The global breeding population is 5.1 million (CCS 13/20).

- American Wigeon (Mareca americana): Populations declined by about 1.5% per year for a cumulative decline of approximately 56% between 1966 and 2019. The global breeding population is 2.7 million (CCS 10/20).

- Black Scoter (Melanitta americana): Listed as a Yellow Alert Tipping Point species (CCS 13/20) and Near Threatened by the IUCN. Its global breeding population is estimated at 900,000.

- American Black Duck (Anas rubripes): Experienced a decline of about 87% in the United States between 1966 and 2019. Its global breeding population is estimated at 700,000.

Comparative Analysis of Population Trajectories

The current status of North American waterfowl presents a strong dichotomy between widely successful grazing and dabbling species, and numerous declining sea duck and specialized continental duck populations.

| Species Group | Status Summary | Population Trend (1966–2019) | Key Concern Score (CCS) |

| Geese (Canada, Snow, Ross’s) | Highly Successful/Overabundant | Rapidly Increasing (+6% to +7% per year) | Low Concern (5 to 10/20) |

| Common Dabblers (Mallard, Blue-winged Teal) | Stable and Abundant | Stable/No Change | Low Concern (7/20) |

| Specialized Dabblers (Pintail, Mottled Duck) | Major Cumulative Declines | Steep Decline (-72% to -73% cumulative) | High Concern (13 to 17/20) |

| Arctic Eiders (Spectacled, Steller’s) | Critically Endangered/Declining | Steep Declining Trends / Perilously Low | Highest Concern (19/20) |

While the Mallard population remains steady at approximately 19 million, species reliant on the Prairie Pothole region have suffered drastically: the Mottled Duck declined by a cumulative 72% (1966–2023), and the Northern Pintail declined by a cumulative 73% in the same period.

Species Recovery

Regarding conservation recovery, the once-endangered Trumpeter Swan population more than tripled between 2000 and 2005 (from 11,156 to 34,803 individuals), achieving “classic conservation success”.

The Redhead population is up 76% from mid-twentieth-century averages, estimated at 1.2 million in 2015, although local populations in the Great Basin declined drastically by 87%.

Major Conservation Challenges

Several common threats contribute to population instability, even for species otherwise rated as low concern:

- Hybridization and Competition: The highly successful Mallard threatens related species through hybridization. This is a severe threat to the Mottled Duck (10% contamination in Florida), and also affects the American Black Duck. Increased contact due to Arctic warming is also leading to more frequent hybridization between Ross’s Goose and Snow Goose.

- Toxicity and Pollution: Many species, particularly divers, are highly vulnerable to pollutants and heavy metals. Ring-necked Ducks are especially susceptible to lead poisoning from ingesting spent shot. Contaminants like DDE and PCBs found in Greater Scaup tissues exceeded guidelines for safe human consumption in the 1990s. Arctic Eiders (Common, Spectacled, Steller’s) are threatened by oil spills, toxic metals, and lead shot.

- Habitat Loss and Degradation: Wetland drainage and urbanization pose perennial threats, especially to species reliant on the critically important Prairie Pothole Region. The disappearance of old-growth forests threatens cavity nesters like the Muscovy Duck, leading to population issues in Mexico.

- Hunting Pressure: While generally managed carefully by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, hunting remains a factor. The Mallard accounts for roughly one-third of all ducks shot. The combined annual harvest for two common teal species (Blue-winged and Green-winged) exceeds 2 million birds. Conversely, abundant species like the Snow Goose are subject to special regulations allowing for extra hunting to curb population growth that is damaging sensitive tundra habitat.

- Invasive Species Impact: Nonnative species like the aggressive Mute Swan (Global breeding population 400,000) compete with and displace native species, posing a dilemma for managers trying to control their numbers.

Conclusion

North American waterfowl show a widening divide between thriving generalists and rapidly declining specialists. Abundant dabblers and geese continue to grow or remain stable, while species tied to vulnerable habitats—especially Prairie Pothole breeders and Arctic sea ducks—have suffered losses exceeding 50% over the past five decades.

Most declines stem from habitat degradation, hybridization with expanding Mallard populations, contaminants, and climate-driven ecosystem changes. Yet the recovery of Trumpeter Swans and the stability of many common ducks demonstrate that targeted management can reverse negative trends.

Protecting key breeding landscapes, curbing pollutants, and safeguarding species’ genetic integrity are now critical. Closing the gap between flourishing and failing species will require shifting from reactive crisis response to proactive, long-term ecosystem stewardship.