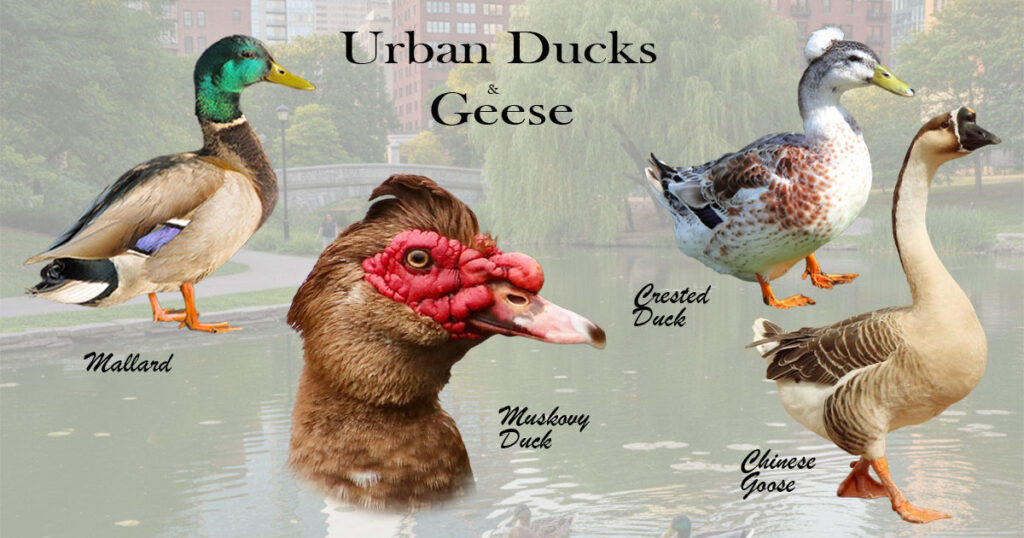

Is that a wild duck, a domestic escapee, or a hybrid? The scene is familiar: you spot a waterfowl in the city park that looks too large, too white, or sports a bizarre bright red warts on its face. This confusion is the reality of urban waterfowl. The Guide to Urban Ducks, Geese, Swans, and Hybrids cuts through the chaos, helping you accurately identify the true Native Waterfowl from the flood of confusing Feral and Exotic species often found in municipal ponds.

This comprehensive guide features the necessary visual comparisons—from the wart-faced feral Muscovy Duck to the wild assortment of Mallard-based hybrid plumage—giving you the tools to confidently identify every bird in the urban flock.

The Urban Habitat Defined

Man-made and modified waterways—including retention ponds, golf course lakes, and heavily managed city parks—offer predictable, year-round access to water and short grasses. This makes them irresistible to resident, non-migratory populations, and the establishment of non-native species.

Key Distinction: Domestic, Native, Exotic/Feral Waterfowl

Understanding the birds in your local park begins with distinguishing their origin:

- Domestic Waterfowl: These are birds—or their descendants—that have been selectively bred by humans over generations for traits such as size, color, or productivity. Some were abandoned or released into the wild. Because of their artificial breeding, they often look very different from their wild ancestors, showing features like pure white plumage, unusual color patterns, or head knobs and crests. Their varied appearance is a common source of identification confusion.

- Native Waterfowl: These are wild species that naturally occur in North America and form part of its native ecology. Some have adapted to human-altered environments, moving freely between municipal ponds and natural wetlands. Examples include the Wood Duck, Black-bellied Whistling-Duck, and true Wild Mallards.

- Feral Waterfowl: A bird that was once domesticated or captive (like a Domestic Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) or a Muscovy Duck (Cairina moschata) that has since escaped or been released and is now surviving and reproducing independently in the wild. Feral waterfowl retain their domestic traits and are the primary source of confusing appearance and hybridization in city parks.

- Exotic Species (Escapees): These are non-native birds that have escaped or been released from zoos, parks, or private collections—such as the Mandarin Duck or Bar-headed Goose. Some fail to survive and disappear, others persist as scattered individuals or small groups, and a few have established self-sustaining (feral or naturalized) populations in parts of North America and elsewhere.

What Is That Weird Duck? Identification in the Municipal Pond

This section tackles the most common and confusing ducks people encounter across North America. Urban waterfowl identification becomes even more difficult given the high degree of hybridization among ducks.

For a breakdown of definitions, please follow: Complete Guide to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of North America.

The Science of Confusion: Why Hybridization is so Prevalent among City Ducks

The high frequency of duck hybrids, which is rare among most other bird families, is the result of unique duck biology meeting human-altered environments.

Most duck species (Anatidae) are still genetically compatible enough (particularly within the Anas genus: Mallards) to produce fertile hybrids. This is the core problem, once a cross occurs, the hybrid offspring remain capable of reproducing with each other or with the parent species (a process called introgression), continuously mixing the gene pool resulting in a wide variety of colors and plumage patterns.

This biological tendency is amplified in urban settings by two key factors, Aggression and human interference.

Aggression: The abundant and dominant Mallard frequently uses forced copulation on females of different species, especially those domestic and non-native ducks found in crowded city parks. Furthermore, the widespread release of domestic fowl introduces mixed, aggressive genetics directly into the environment.

Human interference: When native ducks struggle to find a mate of their own species in fragmented or constrained urban habitats, they often cross with the abundant Mallard. Hybrids in constrained settings cross freely among themselves, accelerating the spread of confusing hybrid traits throughout the urban pond system.

The Kings of the Pond: Feral & Domesticated Ancestors

This group includes species released by humans or bred from farm stock, which are the main source of hybrid confusion.

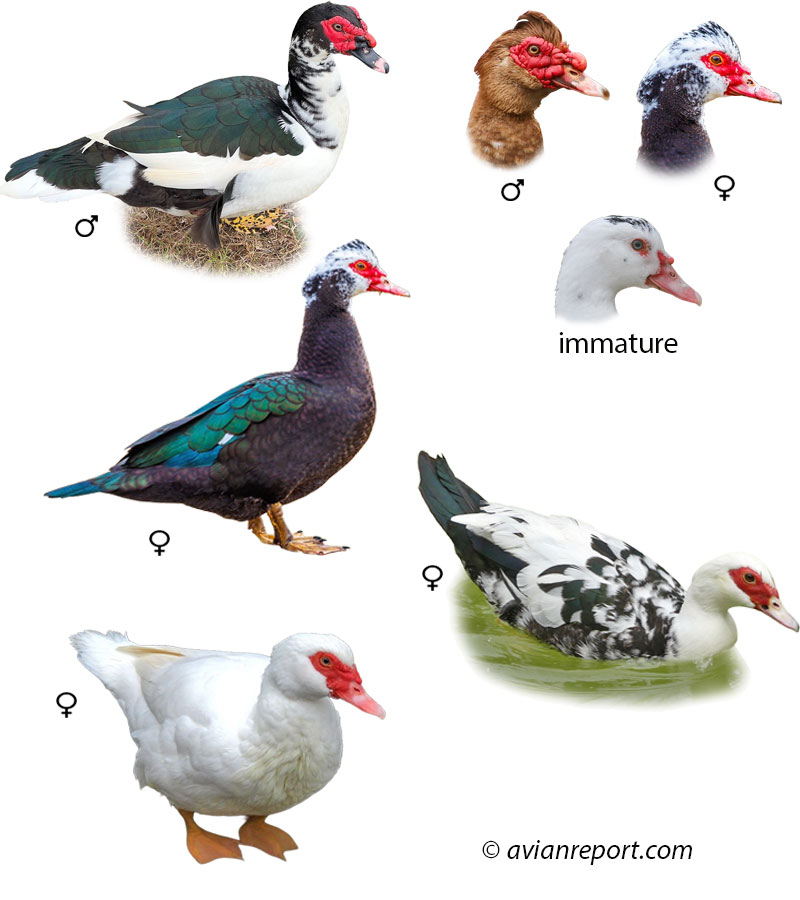

Feral Muscovy Duck

Large and mostly silent, these ducks are easily recognized by the red or black warty growths (caruncles) around their eyes and bill. Muscovy ducks are sometimes nicknamed “ugly ducks,” (males) and are often considered nuisances in city parks and neighborhoods. Unlike Mallards, Muscovy Ducks perch in trees and have a goose-like profile, with long necks and short, waddling legs.

Native to Central and South America, they have now established feral, self-sustaining populations across much of the United States, southern Canada, and in parts of Europe, Australia, and Asia. Muscovy Ducks frequently hybridize with domestic Mallards, producing sterile “Mule Ducks,” which display mixed traits and can be particularly difficult to identify.

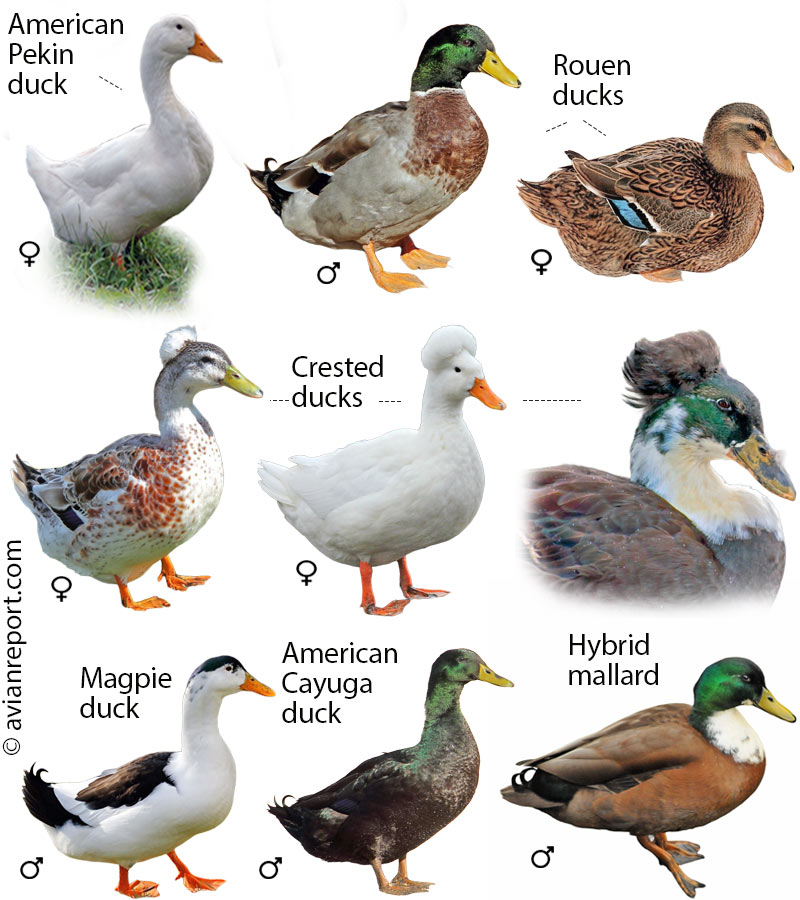

Domestic Mallard Lineage and Hybrids in Urban Settings

Most of the unnaturally large, pure white, mottled, black, or oddly colored ducks you see in municipal ponds and waterways are domestic fowl, all descended from the wild Mallard hat have been selectively bred by humans over generations. Some resemble well known domestic breeds and others are hybrids combining features of multiple domestic varieties. Males Mallards, wild and domestic, show a typical curled feather on the upper side of their tails.

American Pekin Ducks: Pure white, large, with bright orange bills; they are the classic “farm duck” and are easily dumped in city ponds.

Rouen Ducks: Look like very large, heavily built Mallards with muted colors.

Crested Ducks: Look like other domestic mallard types but feature a distinctive puffball of feathers on their heads.

Magpie Duck: A striking black-and-white duck introduced to the United States as a domestic breed in or before 1970.

American Cayuga Duck: An American breed known for its striking black-green iridescent feathers and excellent meat. The drakes have the characteristic curly tail feather of mallard descendants.

Hybrid Mallard (Domestic x Wild Mallard): Plumages resulting from this interbreeding are unpredictable.

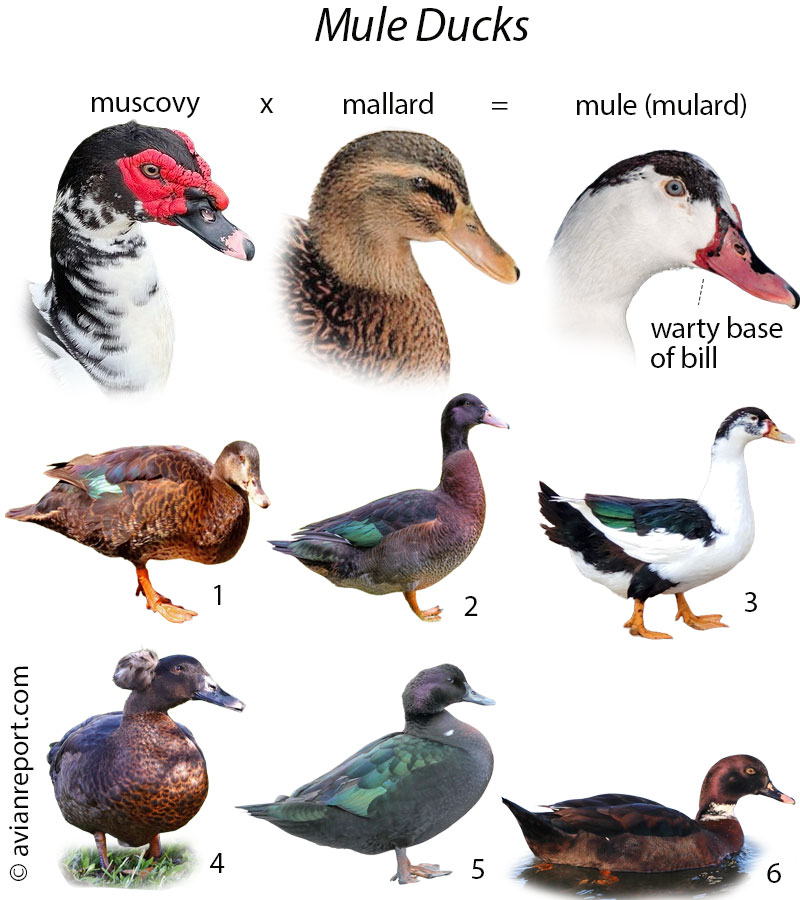

The Mule Duck (or Mulard): The Sterile Urban Hybrid

The Mule Duck (often sold commercially as a Mulard) is a sterile hybrid resulting from the cross between a male Muscovy Duck and a female Domestic Mallard. A far less common is the cross breeding of a male Mallard and female Muscovy, often known as Hinny Duck.

Because Muscovy and Mallard belong to different genera, this cross occurs less frequently naturally in the wild, but it is common in captive settings and on farms. Many Mule Ducks present in urban ponds come from production animals that have been released or abandoned. Unlike hybrids between wild and domestic Mallards, the Mule Duck is sterile (cannot reproduce), meaning every one found is a first-generation cross.

The top section of the image illustrates the head and bill characteristics of the Mule Duck’s parent species. The resulting offspring show a random and unpredictable mix of traits inherited from both parents.

Mule Ducks Key Identification Features

Size: Large, bulky body inherited from the Muscovy, making them noticeably bigger than a wild Mallard.

Caruncles: Exhibits varying amounts of the Muscovy’s red or black caruncles at the base of the bill, a feature completely absent in pure Mallards.

Plumage: Highly variable in color and plumage pattern. Look for the dark-green sheen, longer tail feathers and the absence of the Mallard male’s curled rear feathers.

Bill: Bills are variable (pink, gray, or black), but unlike the Mallards, a pure yellow bill is uncharacteristic.

Individuals 1, 2, and 3 are typical Mule Ducks. Individual 4 is a cross between a Muscovy and Crested Duck. Individual 5 is a female unusually dark green. Individual 6 is a proven Hinny Duck (Male Mallard x female Muscovy). It is smaller and looks like a Mallard with an uncharacteristic plumage.

While some hybrid ducks can be traced to their original parents, the random and unpredictable mixing of traits often produces urban ducks whose parentage is difficult to determine. For example, the duck shown on the right is a baffling mix: Its white scalloping on the sides, orange eyes, reddish breast, and pale belly correspond to a Wood Duck. The iridescent green head and bright orange legs and feet correspond to a Mallard. Finally, the warty growths (caruncles) at the base of the bill correspond to a Muscovy Duck.

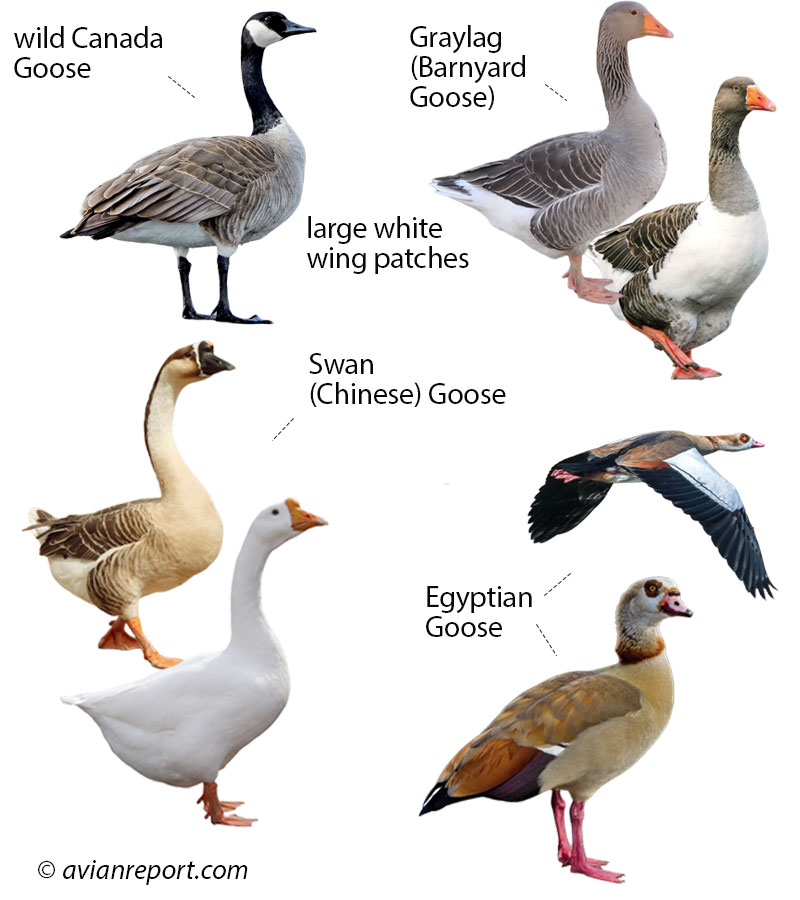

The Geese: Native and Non-Native Residents

While the familiar Canada Goose is the only truly native goose species to commonly breed in North American urban environments, city parks and waterways often host three feral or non-native species. This section covers the abundant native resident and the three most common introduced species—the Graylag Goose, the Chinese Goose, and the established Egyptian Goose—that frequently cause identification confusion.

Canada Goose (Branta canadensis): Native to North America. Large, black-necked goose, often found year-round in urban areas. Status is common to abundant across the continent.

Graylag Goose (Anser anser): Domestic Form – Ancestor of most domestic geese, originating in Europe/Asia. Large, stocky birds, often white or mottled gray. Feral populations are fairly common in city parks.

Chinese Goose (Anser cygnoides): Domestic Form – Domestic breed derived from the wild Swan Goose of Asia. Tall, brown/white goose with a distinct knob at the bill’s base. Feral populations are fairly common locally.

Egyptian Goose (Alopochen aegyptiaca): Native to Africa and introduced as an ornamental species. Striking brown and white goose with distinctive dark eye patches. Feral populations are common in Florida and parts of California.

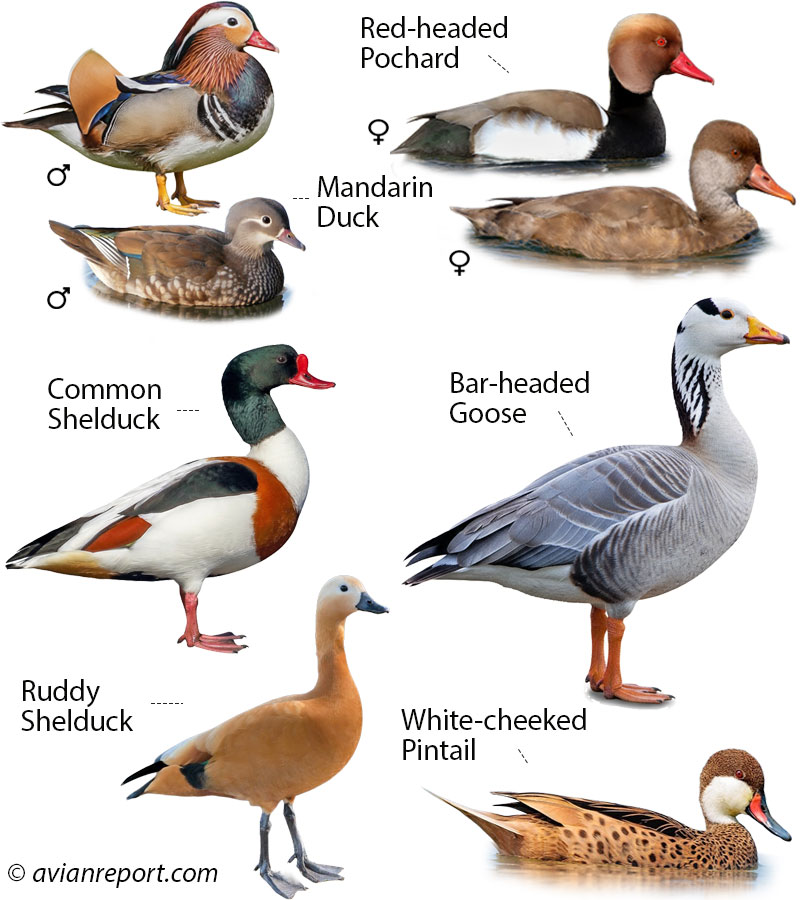

Exotic Waterfowl: Escapes and Ornamentals

The most unexpected sightings in North American waterways are often exotic waterfowl. These are species native to distant continents like Asia or Europe that have established localized populations after escaping from private bird collections, zoos, or farms. While some species are rare transients, a few have proven hardy enough to successfully breed in the wild. This section covers some of the most stunning and frequently reported escapees, which can pose a fascinating identification challenge far removed from our native migrants.

Mandarin Duck (Aix galericulata): Stunningly colorful duck, native to East Asia. Often kept in private collections and escapes are rare but locally established populations exist, making it a highly prized sighting.

Red-headed Pochard (Aythya ferina): A diving duck with a gray body and a bright rufous-red head, native to Europe and Asia. Escapes are rare and sightings are almost always of individuals escaped from private collections.

Common Shelduck (Tadorna tadorna): Large, goose-like duck from Europe and Asia with a striking white, black, and chestnut pattern and a red bill. Escapes are rare, though localized breeding occurs in some regions.

Bar-headed Goose (Anser indicus): Pale gray goose from Central Asia, easily identified by the two prominent black bars on its white head. Escapes are fairly common locally, particularly near large parks or zoos.

Ruddy Shelduck (Tadorna ferruginea): A conspicuous orange-brown shelduck, native to Asia and Europe. Commonly kept in captive collections. Escapes are rare across North America, but reports are increasing.

White-cheeked Pintail (Anas bahamensis): Elegant pintail from the Caribbean and South America. Distinctive for its bright red bill base and white cheek patch. Escapes are rare, occasionally establishing localized breeding.

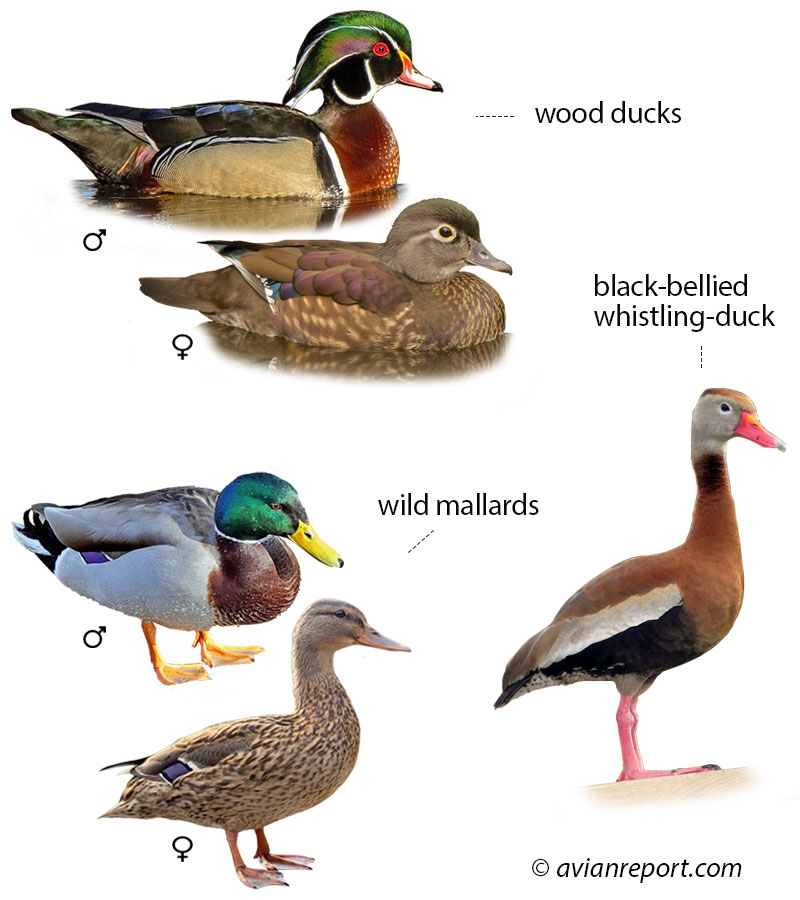

The True North American Natives (Adaptable & Widespread)

This group includes the wild species that successfully inhabit urban green spaces and wetlands. Differentiating the true wild Mallard from its domestic cousins requires noticing its slender, smaller body and the lack of exaggerated colors or size that characterize farm breeds (see above).

Wood Duck (Aix sponsa): Widely considered North America’s most beautiful duck. The male features a striking iridescent crested head and chestnut chest. They are often shy but adapt well to wooded urban wetlands. Their unique habit is nesting in tree cavities (or human-provided nest boxes) near water, a rarity among ducks. Look for them perching high above the water.

The Wild Mallard: The wild type male is iconic with the iridescent green head. However, the urban environment selects for individuals less wary of humans. Wild Mallards are found across almost all of North America.

Black-bellied Whistling-Duck (Dendrocygna autumnalis): A favorite in the Southern U.S., these ducks look more like miniature geese. Key ID features are their bright pink legs and bill, upright posture, and distinct whistling call (especially in flight). They often congregate in large groups along the edges of shallow retention ponds and are less wary of humans than their northern counterparts.

The Urban Swans: Exotics, Ornamentals, and Escapes

Native swans (like the Tundra and Trumpeter) are rarely seen in municipal parks and ponds. Swans are the largest and most prominent waterfowl in urban waterways and are introduced from abroad. This section details the three most common or reported exotic swans, all of which have established, or are attempting to establish, feral populations in North America after escaping from collections.

Mute Swan (Cygnus olor): From Europe and Asia. Large, bright white swan with a distinctive orange bill featuring a large, black knob at the base (knob is larger on males). Frequently holds its neck in an “S”. Widespread feral populations exist, particularly around the Great Lakes and Northeast.

Black Swan (Cygnus atratus): From Australia. Unmistakable; entirely black plumage with a prominent bright red bill tipped in white. They possess a long, graceful neck and red eyes. Due to their popularity in ornamental collections, escapes are frequent. Small, localized feral breeding populations can be found in a few warm-climate areas (like Florida and California).

Black-necked Swan (Cygnus melancoryphus): From Southern South America. Striking white body with a black head and neck. It features a prominent red knob at the bill’s base and a white stripe extending from the bill to behind the eye. Primarily confined to collections. Any sighting in the wild is almost certainly a recent escape and individuals rarely establish long-term populations, making them a very unusual urban visitor.

Community FAQs: How to Be a Responsible Waterfowl Steward

This section is vital for ensuring the health and safety of both the waterfowl and the urban environment across all of North America.

FAQ 1: Why You should Never Feed the Ducks Bread (Health & Habitat)

- Answer Focus: The prohibition is universal and serious. While it may feel like a friendly act, feeding ducks human food causes severe, often irreversible damage.

Angel Wing: This is the critical, most visible consequence. Caused by a diet too high in carbohydrates and low in essential vitamins (like bread, popcorn, or chips), the condition causes a wing joint to twist, leading the flight feathers to permanently stick out. It renders the bird flightless, vulnerable to predators, and unable to migrate.

Nutritional Deficiency: Human snacks offer “junk food” that lacks the calcium, protein, and minerals needed for bone and feather development. This weakens their immune system and shortens their lifespan.

Habitat Degradation: Feeding causes overcrowding, concentrating bird droppings that pollute the water, leading to toxic algae blooms and increased disease transmission (Avian Cholera, Duck Virus Enteritis) among the stressed population.

FAQ 2: Nesting in Your Yard? What to Do About Ducklings

Do not interfere with the natural process. It is common for ducks (especially Mallards) to nest in seemingly bad locations like planters, window wells, or fenced yards, but the mother knows the territory.

- The Golden Rules: Leave the mother and nest alone. Once the ducklings hatch, the mother will lead them to the water. This “Family March” usually happens within 24-48 hours after hatching.

- Intervention: Only intervene if the ducklings are physically trapped (e.g., stuck in a storm drain with no visible way out). In this case, call your local wildlife control or animal services immediately. Do not attempt to move the mother or the nest yourself, as this can cause the nest to be abandoned.

FAQ 3: Geese Management and Reducing Nuisance

Addressing the resident Canada Goose population. These birds thrive in the close-cropped grass of municipal parks and golf courses.

- Deterrents: Non-lethal methods are most effective:

- Habitat Modification: Allow the grass near the water’s edge to grow tall (30 inches or more) to block their sightline and make them feel vulnerable.

- Physical Barriers: Install fences, plastic grid mesh, or motion-activated sprinklers along pond banks.

- Removing Food Sources: Never feed them, as they quickly become aggressive and dependent on handouts.

- Legal Note: Canada Geese are protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (U.S.) and the Migratory Birds Convention Act (Canada). Harassing, injuring, or destroying nests and eggs without a federal permit is illegal.

Conclusions

This guide cuts through the confusion, helping you identify everything from the large, caruncle-faced Feral Muscovy Duck to the sterile hybrid it produces, the Mule Duck. We also cover the most common domestic Mallard variants (like the Pekin and Rouen Ducks) and the non-native duck, geese, and swans that share the pond with the protected Canada Goose. Finally, we detail the essential “Dos and Don’ts” for being a responsible steward, including the serious reasons why you should never feed the ducks bread.

Photo Credits:

The photographic material used in this guide was made available on various websites. Many thanks to Andrew Morffew, Elizabeth Milson, Dennis Church, Wendy Miller, John Benson, Mick Thompson, Vicky DeLoach, Don Hoechlin, Tom Murray, Kenneth Cole-Schneider, Doug Greenberg, Ian Preston, Brian Garrett, John Strung, Becky Matsubara, Judy Gallagher, Sand Diego Zoo, David Inman, Dan Mooney, Ian Preston, Lloyd Davis, Greg Lavaty, Dona Hilkey, Alain Doyle, Aaron Maizlish, Ashley Tubs, Richard George, Ethan Gosnell, Nick, Steve Valasek, Mitch Walters, Julio Mulero, Allan Hack, Mr. Tin, James McWilliams, Myri Bonnie, Charmainet .

References and Sources:

- Allaboutbirds.org

- eBird. (https://ebird.org/)

- Birds of the World: https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/home

- Gill, Frank B., 1994. Ornithology – 2nd Edition, W. H. Freeman and Company.

- Sibley, David, 2000, The Sibley Guide to Birds. Alfred A. Knopf, Publisher.

- The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior, 2001. Chris Elphick, John Dunning, and David Sibley (eds). Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Explore more about: The Ducks, Geese, and Swans of North America.