The osprey is a distinctive bird of prey. Most of its diet consists of live fish, which it captures in a similar manner to some seabirds and kingfishers. The Osprey, on the other hand, uses its talons, not its beaks, to catch fish near the surface of the water. In the spring and fall, ospreys migrate between their breeding and wintering grounds.

- Common name: Western Osprey (Osprey)

- Other names: Fishwawk, Seahawk, Riverhawk

- Scientífic name: Pandion haliaetus

- Order: Falconiformes

- Family: Pandionidae

- Habitat: Bodies of water with fish

- Movements: Migrates in the spring and fall

- Conservation Status: Least concern

- Population trend: Stable

- Global population: ~ 400,000 individuals

- Lifespan: At least 23 years

Meaning of scientific name

- Pandion: Derived from Pandion the mythical Greek king of Athens, grandfather of Theseus, Pandion II.

- heliaetus: Derived from the Greek Hali = Sea and aetos = eagle.

Meaning of common name

The origin of the name Osprey has not been traced with certainty. Some propose that the name derives from the Medieval Latin avis prede (“bird of prey”) through the Norman ospriet. Others trace the name even further back, to the similar-sounding Latin for “bone-breaker”= ossifragus.

Osprey Identification

Identifying an Osprey is relatively straightforward due to its habit of living in open habitats where it is easy to see, its simple plumage, and its stereotyped hunting behavior. Adult birds have a bicolor plumage that consists of a dark brown upperpart and a white underpart. On the breast areas, the white underparts have variable amounts of gray-brown spots and streaks.

An osprey’s head is primarily white, with dark brown side stripes running across the eyes from the base of the bill. Also, the forehead and crown are speckled with gray-brown streaks.

In general, juvenile and adult Ospreys look similar. On their upperparts, juvenile birds have cream-white edges around dark brown feathers and orange eyes. When young birds reach maturity, their plumage loses its pale edge and their eyes turn yellow.

Osprey Size

Ospreys are medium-sized raptors. They are smaller than a bald eagle, about the size of a turkey vulture. Their measurements are as follows:

- Length: From the tip of the beak to the tip of the tail, its length varies between 21.6 and 23 inches.

- Wingspan: It is the distance between the tips of the outstretched wings and varies between 57 and 67 inches.

- Weight: Males and females have different weights. The male is smaller and weighs between 2.1 and 3.9 pounds. Females weigh between 2.6 and 4.5 pounds.

Summary of Measurements:

| Body Length | Weight | Wingspan |

| 21.6 – 23 in | 2.1- 3.9 lb (male), 2.6 – 4.5 lb (female) | 57 and 67 inches |

Other fieldmarks

- Ospreys have bushy feathers that resemble a nuchal crest on the nape area.

- Ospreys have long, narrow arched wings that resemble the shape of an M in flight.

- Ospreys have a dark gray tail with a lighter gray or whitish bar. The tail is relatively long.

- Unlike other birds of prey, Ospreys do not have a supraorbital bone, also called a supraciliary bulge above their eyes. Birds of prey look fierce due to this distinctive facial feature.

Bare parts

- Most of the beak is black. The cere and base have a bluish cast.

- Legs and feet are pale with a faint blue tinge.

You can learn more about Osprey identification in this separate article.

Male and Female plumages

Males and females Ospreys have similar plumages. The subtle differences overlap between sexes making it difficult to identify the bird’s gender based on their plumage.

The chests of females are more densely marked with spots and streaks than in males. A dense band of spots and streaks forms across the chest of some females. Males’ chests usually have fewer dark streaks, and some are plain white.

Nevertheless, there are many individuals with an intermediate amount of dark spots and streaks on the chest, which makes it difficult to determine the gender of the individual.

Females tend to have more bars and spots on the underwing, but there is much overlap between the two sexes.

Both male and female Ospreys have the same plumage throughout the year.

Birds Similar to Ospreys

Ospreys are similar to Bald eagles, red-tailed hawks, and turkey vultures in North America.

Birds in the wintering grounds that look like ospreys include the Peruvian and Blue-footed boobies, kelp gulls, and only superficially the black-and-white hawk-eagle.

Osprey subspecies

Ospreys are widespread throughout the world except for Antarctica. Of the four known Osprey subspecies two occur in the Americas and are collectively known as Western Ospreys:

- Pandion haliaetis haliaetus: This subspecies is distributed throughout Eurasia, northern Himalayas, and North Africa.

- P. h. carolinensis: This subspecies is found in the Americas, and it is the largest and darkest of all Osprey subspecies.

- P. h. ridgwayi: This subspecies is resident in the Caribbean Islands. It is characterized by its pale coloration and poorly defined dark stripe across the eye.

- P. h. cristatus: This subspecies founs in the coastline and some large rivers of Australia and Tasmania. It is the smallest in size and is characterized by having the darkest chest and more dark feathers on the forehead and crown.

Voice

Ospreys have a wide repertoire of calls and other types of voices. Calls, whistles, and screeches are often specific to a type of interaction between males and females.

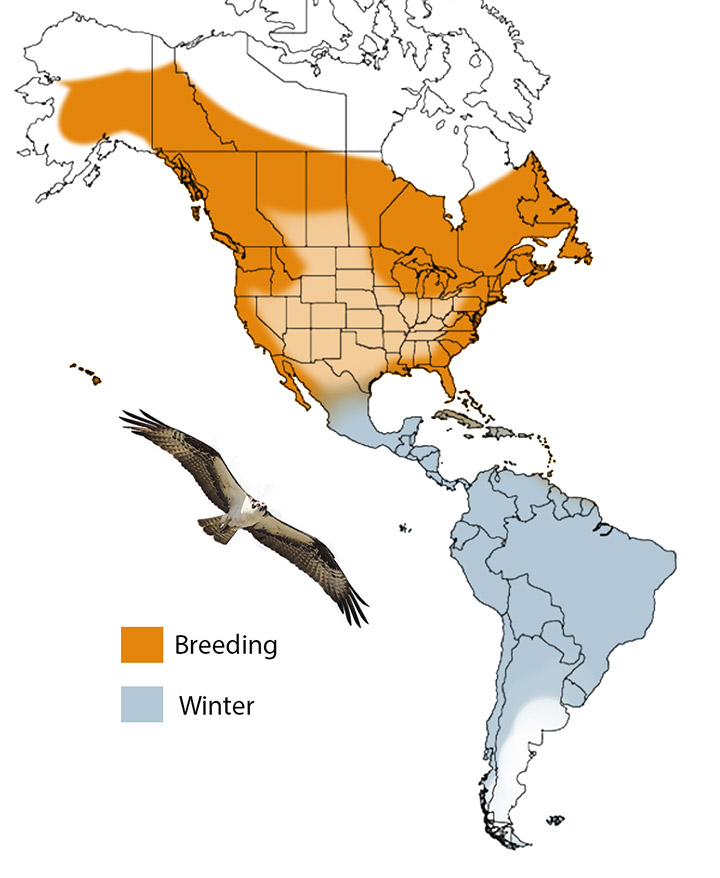

Osprey distribution in the Americas

Ospreys of the Americas, also known as Western Ospreys, are found throughout North, Central, and South America. It is absent from the Antarctic Region of North America and rare in the southern cone of South America.

Breeding range

- Most Ospreys breed in the United States and Canada.

- Small numbers breed in northwestern Mexico, Cuba, the Yucatan Peninsula, and smaller Caribbean islands north of Cuba.

- In recent decades, ospreys have expanded their breeding range in all directions.

Wintering range

- Wintering areas for Ospreys extend from the lower half of the United States to Southern Chile.

- Mexico, the Caribbean Islands, Central America, and most of South America are the main wintering grounds for Ospreys.

- Year-round resident populations breed and spend the winter in the same region.

Osprey Migration

Ospreys migrate south to north in the spring and north to south in the fall. Their migration patterns vary by region. Ospreys migrate long distances, but some only travel a few hundred miles, and some populations do not migrate at all.

Spring migraion

- As average daily temperatures become more favorable, Ospreys begin to arrive in South Florida.

- Osprey begin to lay eggs between a week to 15 days after arriving to their breeding sites.

- About three months after arriving in South Florida, Ospreys reach Canada and Alaska by late May.

- The males arrive first, followed by the females.

Fall migration

- Birds migrate south roughly in the same manner as they arrived. The birds of the southern states migrate south earlier than those of the northern states.

- As soon as the chicks leave the nest, the females begin the fall migration.

- Males stay longer to continue feeding their newly fledged young and initiate the fall migration later.

More details about Osprey migration can be found in a separate article.

Habitat

Ospreys can be found in coastal estuaries, salt marshes, lakes, reservoirs, lagoons, and rivers. Regardless of whether the water is fresh, brackish, or saltwater, they prefer shallow waters with tall trees, perches, and structures suitable for building their bulky nests.

While ospreys are always associated with water, they can also be spotted away from it when migrating and moving between feeding grounds.

Osprey diet

Ospreys eat mostly live fish (99%), which they catch using a technique unique to birds of prey.

A stereotyped Osprey feeding strategy combines techniques used primarily by seabirds and kingfishers. The method involves looking for a fish near the surface of the water, diving, and plunging into the water to catch it.

In contrast to seabirds and kingfishers, Ospreys catch their fish with their talons, not their beaks.

Generally, ospreys prey on the more abundant fish types that are easier to catch in an area. Osprey diet studies found that, in some regions, ospreys prefer to catch certain types of fish in higher proportions than what is available in the foraging area.

The size of the fish they catch also depends on what is available. However, multiple field studies of foraging Ospreys found that the most frequently caught and successfully consumed fish ranged from 136 g to 408 g or 0.3 lb to 1 lb.

Visit a separate article for more information on osprey feeding.

Breeding

Ospreys form monogamous relationships that generally last for as long as both pair members survive. In the event that either the male or female dies or disappears, the surviving bird will find another breeding partner.

Mated birds return to their previous year’s nest after not seeing each other during the winter. First-time breeders generally form pairs at the breeding grounds before building a nest.

Nesting begins and ends at different times in the breeding range of ospreys. The birds of the south begin breeding in February, while those of Canada and Alaska begin breeding in May-June. However, the average Osprey breeding season or nesting season, which is defined as the time between the first egg laid and the first fledgling, lasts about 13.4 weeks (3 months).

Pair formation and mating

- First-time breeders form a pair in the breeding grounds.

- Males arrive first and pick a potential nesting site.

- Mated pairs return from the wintering grounds to meet at the nest they used the year before.

- Copulations begin as the new pairs build the nest and mated pairs rebuild their existing nest. Photo: Assateague Island National Seashore.

Nest building

- Nest building starts as soon as the pair is formed.

- New nests may take about 14 days to finish.

- Mated pairs begin adding nesting material to their existing nest soon after they arrive.

- Mated pairs may take a week to have the nest ready for the eggs.

- The male collects the nesting material while the female arranges it on the nest. Photo: Recreation-Gov.

Egg laying and incubation

- Inexperienced new breeders may take up to 20 days to lay eggs after arriving.

- Mated and experienced birds may start laying eggs a week after arriving to the breeding grounds.

- Female Ospreys lay 2 to 5 eggs, but three eggs is the norm.

- The female incubates the eggs most of the time while the male brings food and protects the nest. Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program NY.

Hatching, growth, and fledging

- It takes an average of 39 days between the first egg laid and the first egg that hatches, ranging from 35 to 43 days.

- After the chicks hatch, the male continues to provide food for the female and the young.

- As the nestlings grow, the female begins to help feed them.

- From hatching to the time of fledging, the average is 55 days, ranging from 50 to 60 days.

- One or two weeks after the nestlings have fledged, the male continues to feed the fledglings, while the female begins her migration south. Photo: Mark Harper.

Nest predators

Ospreys have relatively few predators as adults. However, their nests are vulnerable to diurnal and nocturnal predators that take their eggs and nestlings.

Diurnal predators include mainly bald eagles that can take young ospreys from the nest. Crows can steal Osprey eggs from unattended nests.

Osprey nests are more vulnerable to nocturnal predators including raccoons and great-horned owls. These predators attack at night when the adult Ospreys have limited ability to defend their eggs and young.

It’s not uncommon for Osprey nests to be found along lakes and seashores, which are also popular areas for real estate development. Urban development usually attracts a substantial number of raccoons, which are more likely to raid the Osprey nests.

The great-horned owl is perhaps the most significant Osprey nest predator. Owls attack nests of ospreys, stealing young and even killing adults. In a study of nesting ospreys, great-horned owls preyed on about 20% of nestlings.

A separate article about osprey breeding provides more detailed information.

Lifespan/longevity

Ospreys have relatively long lifespans. The oldest male osprey died at 25 years and two months. It was first banned in Virginia. The oldest female osprey died at 23 years. She was banded in Maryland and died in the same State, according to “Longevity Records of North American Birds,” compiled by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland.

Ospreys’ probability of survival from one year to the next is high. A study (Poole, et al., 2002) on osprey survival determined that 80 to 90% of adults are likely to survive from one year to the next. Young birds showed less probability of survival, with 60% of birds likely to survive from one year to the next.

Population size

According to the Partners in Flight Science Committee (2021), the estimated osprey population in the Americas is 400,000 mature individuals. The committee further estimates the global population at 1,200,000 mature individuals.

Osprey behavior

In most of North America, Ospreys are present only during the months of spring and summer. During that relatively short time, a breeding pair has to build or rebuild a nest, incubate the eggs, raise their young, and get ready to migrate before the low temperatures of the winter make fish inaccessible.

Ospreys spend most of their time interacting with each other and fishing.

Interactions between Ospreys

- As part of their interactions Osprey give calls, schreeches, and chirps loudly and continuosly.

- Ospreys have different call types for specific interactions.

- The female stays in the nest most of the time, while the male protects the nest from intruding Ospreys and predators.

- Ospreys can often be seen flying over or perched on utility poles and other manmade estructures. Photo: Matthew Davies.

Fishing to feed others and self

- Ospreys are often observed carrying fish in their talons.

- Males do the majority of the fishing because they feed the female during incubation as well as their young.

- Ospreys eat only 300 grams of the fish they catch, regardless of its size, and discard the rest.

- Ospreys hunt fish throughout the day but prefer to do so during tide changes.

- Ospreys are excellent anglers. Their success rate varies between two and eight fishes caught every ten dives. Photo: Shirley Freyre.

Relationship with humans

Competition for fish

Local fishermen often perceive Ospreys as competitors because they observe them taking fish after fish. Poole (1989) examined the osprey’s fish consumption along with the fish available to fishermen and found that only a small percentage of the available fish was taken by the osprey. Moreover, ospreys are more likely to take small fish, which humans do not seek out.

Osprey conflict with fish farmers

In the wintering grounds, ospreys conflict with fish farm owners because they catch fish from their farms and make them their favorite fishing spots.

Ospreys, unfortunately, do not fare well in this conflict. A small fish farm may cover the fish pool and use other techniques to keep ospreys from taking fish. Covering many pools is more challenging in large farms where fish farmers often shoot the problem osprey.

Annually, approximately 14,000 ospreys are shot and killed by fish farmers in the wintering grounds, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. As data from several countries were unavailable, the number may underestimate the magnitude of the problem.

Osprey role in the ecosystem

An osprey’s role in the ecosystem includes:

Bioindicator: Ospreys are diet specialists that eat only fish. Their presence and abundance reflect the productivity of the habitat. A decline in population size or absence of Ospreys may indicate changes in fish species composition and abundance, changes in water quality, excessive pollution, or ecosystem deterioration.

Breeding opportunities for other birds: Ospreys build some of the largest nests of any North American bird. Small birds such as European starlings, barn swallows, house sparrows, and grackles nest in the chambers and crevices created below the nest’s top. These birds benefit from the protection of ospreys when they are present since they fend off any predator that approaches their nest.

Larger birds that breed in similar nest types use the top of osprey nests. Great-horned owls, bald eagles, hawks, herons, common ravens, and even Canada geese have been observed using Osprey nests for breeding.

Some of these secondary nest users breed before the Ospreys return for the nesting season. Others, such as bald eagles and great-horned owls, usurp Osprey nests for their use forcing them to build a new nest.

Conservation Status

Ospreys have gone through a dramatic period of population decline and recovery. Ospreys were in danger of extinction throughout most of their range.

During the 1950s to 1970s, Osprey populations declined by 90% along the US East Coast, considered the most significant stronghold for the species. Habitat destruction and degradation, illegal shooting, and the contamination of its food source due to the use of the pesticide DDT decimated the Osprey population.

Ospreys and other large raptors, also affected by DDT, benefited from the conservation measures provided by the Endangered Species Act, including the banning of DDT. Ospreys no longer need the protection of the Endangered Species Act because their populations are healthy and growing.

Ospreys are still listed as threatened, endangered, or a species of concern in several US states. Each state has laws that protect ospreys to varying degrees.

Ospreys are also protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) and Appendix II of CITES.

The MBTA states that: It is unlawful for any person to take, possess, import, export, transport, sell, buy, trade or offer for sale, buy or trade any migratory bird, or the parts, nests or eggs of such birds except under the terms of a valid permit issued in accordance with federal regulations.

References

- Bierregaard, R. O., A. F. Poole, M. S. Martell, P. Pyle, and M. A. Patten (2020). Osprey (Pandion haliaetus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- Hagan, J. M. and J. R. Walters (1990). Foraging behavior, reproductive success, and colonial nesting in Ospreys. Auk 107:506–521.

- Henny, C. J., R. A. Grove and J. L. Kaiser. (2008b). Osprey distribution, abundance, reproductive success and contaminant burdens along lower Columbia River, 1997/1998 versus 2004.

- Martell, M. S., C. J. Henny, P. E. Nye and M. J. Solensky. (2001a). Fall migration routes, timing, and wintering sites of North American Ospreys as determined by satellite telemetry. Condor 103:715-724.

- Poole, A. 1989. Ospreys: A Natural and Unnatural History. New York: Cambridge University Press.